Plato’s Republic Books 9-10: The Triumph of Virtue

This essay concludes our discussion of the Republic by elucidating Plato’s closing arguments for the contention that justice is an intrinsic, rather than extrinsic, good.

After setting forth a taxonomy of constitutions and the types of individuals that correspond to them, Plato is now in a position to return to the central question of the Republic: Is justice an intrinsic good, or is it valued only for its extrinsic effects? Is the mere possession of justice sufficient for human happiness? And does the mere fact that a man is unjust suffice to make him miserable? Plato answers these questions in the affirmative, articulating three arguments for the contention that justice is an intrinsic good.

Argument 1: The Comparison Argument

Socrates’ first argument consists of a straightforward comparison of the lives of the aristocratic and tyrannical character types to determine which is happier. On the one hand, the aristocratic soul, corresponding to the ideal city, is ruled by reason. His mind sets the direction for his life, allowing him to consider the various putative goods before him, and choose those most in alignment with the eternal form of the Good. His spirited element follows reason’s lead, applying its power and ferocity to implementing the mind’s chosen life path. Such a man will be fearless in the pursuit of his goals and will not easily be discouraged by the obstacles he faces in the material world. Finally, because it is guided by reason and spirit, his appetitive soul will also flourish. He will cultivate his necessary and lawful desires, allowing them to grow freely and thrive; and he will be sure to keep whatever unnecessary and lawless desires he might have, if any, in check, so that they do not choke out his more salutary ones. Because of this, he will have a good chance of actually satisfying his appetites and building a solid and successful material life.

On the other hand, the tyrannical soul is ruled from below by lawless passion. Like the tyrannical city, he will be enslaved, since the very worst elements of his soul, its “maddest and most vicious” desires, will reign over it (577d). He will set his life’s course by desires cut off from from the good of intellect, seeking deceptive and ephemeral goods which serve to bring him only misery. Such a condition is illustrated poetically by Dante when he depicts Satan, the greatest tyrant of all in the Christian tradition, not as a powerful lord of hellfire, but as an impotent monster encased in ice. Forever weeping and devouring, and forever unsatisfied.

And, just like the tyrannical city, not only would such a soul be enslaved, but it would also be marked by disorder and regret. This follows of necessity, since, if one follows the random dictates of lawless passions, one is sure to live a disordered life and come to regret (i) either failing to attain one’s goals or (ii) the attaining of them (since they do him only harm). He will be forever poor and unsatisfied, powerless to satiate his cravings (578a). In short, Socrates claims that the life of the tyrannical man, “maddened by his desires and erotic loves”, is one of “wailing, groaning, lamenting, and grieving” (578a). Far from being the happiest, the tyrannical man would thus be “the most wretched of them all” (578b).

Socrates then goes on to argue that things become even worse for the tyrannical soul if fortune makes him to a political tyrant as well. For, the tyrant lives within a political landscape that fundamentally contradicts his desires. The tyrannical soul, in its madness, seeks to be master of all. But, as Socrates explained earlier, tyrannies must justify and establish themselves on democratic promises. He must legitimate his rule by denouncing the legitimacy of all rule. Socrates thus likens tyrant’s situation to that of a man who wants to be a slave master. If he lives in a city that will protect his interests, he will have little to fear from his slaves, since the rest of society would enforce his claims upon them and punish them if they were to rebel. But, if he were taken to a remote location where no one else would enforce his claims to power, he would find himself in great danger, since his slaves outnumber and could easily overpower him. Socrates adds that the situation is even worse for the tyrant in a democracy, because, rather than being alone in the wilderness, he would be surrounded by neighbors who “wouldn’t tolerate anyone to claim that he was the master of another and would inflict the worst punishments on anyone they caught doing it” (579a). The tyrant would thus be surrounded by “vigilant enemies” (579b). He would live like a prisoner in his own home, being forced to “pander to slaves” (579a), “fawn on them”, and “promise them lots of things” (579a), and always on guard against the enemies which surround him. Socrates thus concludes:

“In truth, then, and whatever some people may think, a real tyrant is really a slave, compelled to engage in the worst kind of fawning, slavery, and pandering to the worst kind of people. He’s so far from satisfying his desires in any way that is clear… that he’s in the greatest need of most things and truly poor. And, if indeed his state is like that of the city he rules, then he’s full of fear, convulsions, and pains throughout his life” (579d-e).

Hence, by comparing the life of the aristocratic soul to that of the tyrannical, we can see that the just man is happy, and the tyrant wretched. Justice, then, is sufficient for happiness, and injustice for misery. Socrates summarizes:

“The best, the most just, and the most happy is the most kingly, who rules like a king over himself, and … the worst, the most unjust, and the most wretched is the most tyrannical, who most tyrannizes himself and the city he rules” (580c).

Argument 2: The Adjudication of Pleasures Argument

Socrates’ second argument turns on his doctrine of the tripartite soul and the kinds of people ruled by its three elements. According to Socrates, the human soul is composed of three parts: the rational, the spirited, and the appetitive, each having its own corresponding desire and pleasure (580d).

We learn through the rational part of the soul (580d). It desires to learn and know the truth (581b) and takes pleasure in grasping the eternal (582c). We get angry through the spirited part of the soul. It desires “control, victory, and high repute” (581a), and takes pleasure in victory and honor (581b). And, finally, we attend to our multiform bodily needs through the appetitive element (580e). It desires “food, drink, sex, and all the things associated with them” (580e), and secondarily, money, since “such appetites are most easily satisfied by means of money” in our society (581a). It takes pleasure in all such things (581a).

People can then be classified according to the element of soul that reigns within them. Those of the philosophical type will be ruled by the rational element, those of the spirited type by the spirited element, and those of the appetitive type, by the appetitive. Note how each type will assign a different value to different kinds of pleasure. The philosopher will claim that the bodily pleasures and the pleasures of honor and reputation are nothing compared with the pleasures of knowing the eternal. The spirited man will similarly despise bodily pleasures as vulgar and philosophical pleasures as “smoke and nonsense” compared with the pleasures of victory and honor (581d). And, finally, the appetitive man will “say that the pleasure of being honored and that of learning are worthless compared to that of making a profit” and using it to satisfy his bodily desires (581d).

Prima facie, this situation presents us with an impasse regarding which form of pleasure is, in fact, superior, since each type of person insists that the pleasure associated with his own particular form of desire is the greatest. We thus need an argument to determine which of these three pleasures is, in fact, superior. Now Socrates’ own argument turns on this fact that the criterion for determining which of these pleasures is truly superior is one dictated by reason. To demonstrate that one type of pleasure is better than another, it would not suffice, for example, to bribe people to say it was so or to beat them into submission. Rather, to rationally settle the debate, one would have to appeal to experience, reason, and argument. In other words, the debate can be rationally decided only by philosophical means. As a result, of the three types of men, the philosopher is best situated to resolve the dispute and, consequently, his testimony holds the most value.

Consider first, the question of experience. Of the three types, the philosopher alone has tasted of all three kinds of pleasure. In living his life, he will have at some point satisfied some of his bodily desires and know what it feels like to be honored, but he will also have partaken of the eternal Love the moves the sun and other stars (582b). This is not the case for the other two types. For though the spirited man has partaken of bodily pleasure and declared those of victory and honor to be superior, he has not tasted the ecstasy of the eternal. And the appetitive man, experiencing only the pleasures of the body, has tasted neither victory nor the joy of philosophy. So, of the three types of man, only the philosopher has the relevant experience by which to make a proper judgment regarding rank order of pleasures. And his verdict is that that those of the mind are superior, followed by those of spirit, and then the bodily appetites.

Socrates makes a similar case regarding reason and arguments. To rationally adjudicate the rank order of these pleasures, we will need to use reason and logical argumentation. And it is precisely the philosopher in whom reason rules, and it is he who has devoted his life mastering its logical craft (582d). If determining the rank order of desires were a pie eating contest, the advice of the appetitive man might prevail. Likewise, if it were a trial by combat, we would likely pay heed to the council of the spirited man (582e). But, since this is a question of truth, the skills of the philosopher are the most relevant here. So, again, the philosopher would be in the best position to determine which pleasures are superior. And he declares that they are the pleasures of the Absolute.

Argument 3: The Qualitative Pleasure Argument

Socrates dedicates his third and final argument “in Olympic fashion to Olympian Zeus the Savior” (583b). This argument turns on the nature and quality of the pleasures in question. Socrates contends that neither the pleasures of the body, nor even those of the spirit, are pure pleasures. They are mere shadows of the true pleasure enjoyed by the rational soul. Socrates takes this argument to be the strongest and most insightful, constituting “the greatest and most decisive of overthrows” (583b).

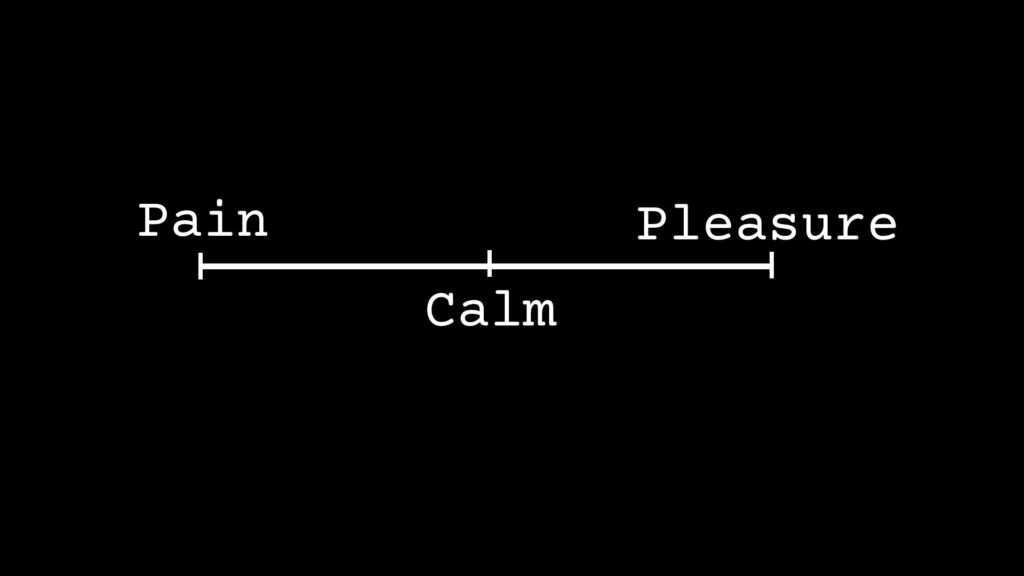

Socrates first notes that pain and pleasures are opposites, and that calm exists as a kind of intermediate state between the two (583c). We would thus have three distinct states: pain, pleasure, and between the two, calm.

Yet, Socrates observes that it is possible to misidentify these three states. He points to the example of the sick and those in chronic pain. These people would identify health and the mere absence of pain as the greatest of pleasures. Sick people, for instance, say “that nothing gives more pleasure than being healthy, but that they hadn’t realized that it was most pleasant till they fell ill” (583c). Similarly, those in great pain maintain “that nothing is more pleasant than the cessation of their suffering” (583d). And Socrates observes that “you find people in pain praising, not enjoyment, but the absence of pain and relief from it as most pleasant” (583d). So, the ill and those in chronic pain come to identify the state of calm with that of pleasure (583d).

But Socrates argues that such an attribution would be a mistake. Consider someone who has been living in a state of pleasure. If this pleasure were to suddenly disappear, and he dropped into a state of calm, he would claim that state was painful (583e). If both groups of people were correct, then the state of calm would be both pleasurable and painful. But we already stipulated that these two states are opposites and so they couldn’t be co-exemplified in the same state in the same manner. If the declarations of these people were accurate, an intermediate state that is neither pleasant nor painful, would be both pleasant and painful. Hence, Socrates concludes that such declarations are mistaken (584a) and that people make false judgements in these matters because of their relative perspectives. Socrates observes:

“When the calm is next to the painful it appears pleasant, and when it is next to the pleasant it appears painful. However, there is nothing sound in these appearances as far as the truth about pleasure is concerned, only some kind of magic” (584a).

Socrates argues that pure pleasures, in contrast, don’t arise from pain, and pure pains don’t arise from pleasure. He points to certain pleasant smells as an example of pure pleasures (584c). He observes:

“The pleasures of smell are especially good examples to take note of, for they suddenly become very intense without being preceded by pain, and when they cease they leave no pain behind” (584b).

With this conceptual framework in place, Socrates goes on to argue that the so-called pleasures of the body are, at best, constituted by the mere absence of pain, and thus are not pure pleasures (584c).

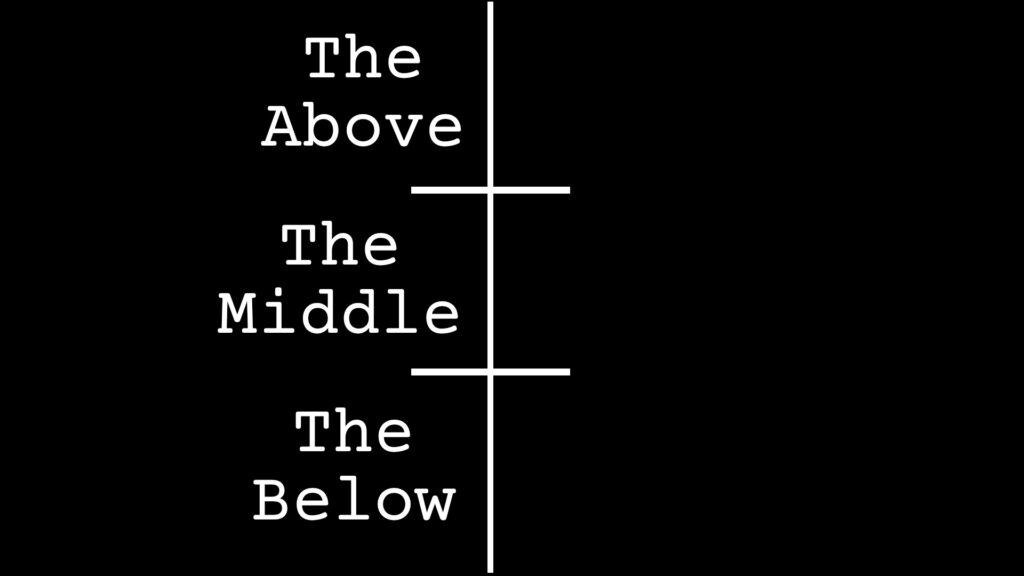

Socrates likens the situation to one in which a person dwells in one of three regions: The Above, The Middle, and the Below.

If one was brought from Below to the Middle, he would correctly perceive that he moved upward and thus conclude that he now resides in the Above. He would be ignorant of the fact that he lives only in the Middle region, and that the true Above still lies beyond him. He would make this mistaken inference “because he is inexperienced in what is really and truly up, down, and in the middle” (584e). Socrates argues that the same holds true for those who deem the pleasures of the body to be ultimately real. He explains:

“Is it any surprise, then, if those who are inexperienced in the truth have unsound opinions about lots of other things as well, or that they are so disposed to pleasure, pain, and the intermediate state that, when they descend to the painful, they believe they are truly and really in pain, but that, when they ascend from the painful to the intermediate state, they firmly believe that they have reached fulfillment and pleasure? They are inexperienced in pleasure and so are deceived when they compare pain to painlessness, just as they would be if they compared black to gray without having experienced white” (584e-585a).

Socrates further elaborates this point by comparing various corresponding desires of body and soul. According to Socrates, hunger and thirst are indicative of bodily emptiness (585b), but ignorance and lack of sense are indicative of emptiness of soul (584b). And just as one satisfies his hunger by eating, so too does the other nourish himself and strengthen his understanding in the truth (584b). And, when we compare these two kinds of filling up, we see that the filling up of the soul is ontologically superior to the filling up of the body (584b). Socrates explains:

“And which kinds partake more of pure being? Kinds of filling up such as filling up with bread or drink or delicacies or food in general? Or the kind of filling up that is with true belief, knowledge, understanding, and, in sum, with all of virtue? Judge it this way: that which is related to what is always the same, immortal, and true, is itself of that kind, and comes to be in something of that kind—this is more, don’t you think, than that which is related to what is never the same and mortal, is itself of that kind, and comes to be in something of that kind?” (584c).

Socrates then uses this fact to show that the pleasures of the soul have more reality than those of the body. For, Socrates defines true pleasure as arising from being filled with what is appropriate to our nature (584d). And, so, since “that which is more, and is filled with things with things that are more”, is more filled than “that which is less and is filled with things that are less”, the soul enjoys truer pleasures than those of the body (584e).

Yet, the majority of men have no idea of this, content to live their lives as mere beasts in pursuit of bodily pleasures. Socrates observes:

“Therefore, those who have no experience with reason or virtue, but are always occupied with feasts and the like, are brought down and then back up to the middle, as it seems, and wander in this way throughout their lives, never reaching beyond this to what is truly higher up, never looking up at it or being brought up to it, and so they aren’t filled with that which really is and never taste any stable or pure pleasure. Instead, they always look down at the ground like cattle, and, with their heads bent over the dinner table, they feed, fatten, and fornicate. To outdo others in these things, they kick and butt them with iron horns and hooves, killing each other, because their desires are insatiable. For the part that they’re trying to fill is like a vessel full of holes, and neither it nor the things they are trying to fill it with are among the things that are” (586a-b).

Rather, the majority waste their lives chasing shadow pleasures (586c). A similar case holds for the spirited man who pursues a life of honor. For his pleasures too are mixed. Socrates asks, “doesn’t his love of honor make him envious and his love of victory make him violent, so that he pursues the satisfaction of his anger and of his desires for honors and victories without calculation or understanding?” (586d). If one is forever seeking honor, then one always wants more of it. There is always another battle to be won and another land to conquer, and, as a result, one is always envious of those who have won those battles and conquered those lands. Likewise, to flourish as a warrior and cutthroat competitor, one must cultivate a certain violent tendency in one’s soul. But this violent tendency dampens one’s ability to rationally engage with the world, thus cutting one off from the true pleasures of the intellect.

Thus, Socrates concludes that it is the philosopher, the person ruled by the rational element, who partakes of the truest pleasures. Not only will the sage enjoy the ecstasy of the eternal, but his spirited and appetitive desires will also be more satisfied than they would be if they were alienated from reason, as they are in the appetitive and spirited man.

“Then can’t we confidently assert that those desires of even the money-loving and honor-loving parts that follow knowledge and argument and pursue with their help those pleasures that reason approves will attain the truest pleasures possible for them, because they follow truth, and the ones that are most their own, if indeed what is best for each thing is most its own?…. Therefore, when the entire soul follows the philosophical part, and there is no civil war in it, each part of it does its own work exclusively and is just, and in particular it enjoys its own pleasures, the best and truest pleasures possible for it…. But when one of the other parts gain control, it won’t be able to secure its own pleasure and will compel the other parts to pursue an alien and untrue pleasure (586d-587a).”

The just man, i.e. the aristocrat of spirit, will thus lead the most pleasant, fine, and graceful life (588a). And, since the life of the tyrant is the farthest removed from that of the aristocrat, the tyrant’s life will be furthest removed from true pleasure (587b).

Illustration: Three Creatures Inside a Human Disguise

So, in light of these arguments, Socrates concludes that, contrary to the contention made at the outset of the Republic that the completely unjust man is happy so long as he is believed to be just, injustice is an intrinsically a miserable state, and justice a happy one. He completes his account with an illustration, asking us to imagine that three very different creatures live behind a human disguise. One of these creatures is a “multicolored beast with a ring of many heads” who “can grow and change at will”. Some of these heads are those of gentle animals, but others those of savage beasts. (588c). This multiheaded creature corresponds to the appetitive part of the soul. The second creature is a lion and corresponds to the spirited part of the soul. And finally, the third creature is a human being and corresponds to the rational part of the soul.

Given such an image, the person who maintains that the cultivation of injustice is a profitable way of life for a human, would be recommending the following course of action:

“He is simply saying that it is beneficial for him, first, to feed the multiform beast well and make it strong, and also the lion and all that pertains to him; second, to starve and weaken the human being within, so that he is dragged along wherever either of the other two leads; and third, to leave the parts to bite and kill one another rather than accustoming them to each other and making them friendly” (588e-589a).

In contrast, the person who contends that the just life is best maintains:

“First, that all our words and deeds should insure that the human being within this human being has the most control; second, that he should take care of the many-headed beast as a farmer does his animals, feeding and domesticating the gentle heads and preventing the savage ones from growing; and, third, that he should make the lion’s nature his ally, care for the community of all his parts, and bring them up in such a way that they will be friends with each other and with himself” (589b).

Socrates takes the superiority of this latter course of action to be self-evident. No external reward could be worth “enslaving the best part of” yourself “to the most vicious” (589e). For, to enslave the most divine part of yourself to the most godless and polluted would be a wretched state which no amount of gold could ameliorate (590a).

The Extrinsic Rewards of Justice

Worldly Rewards and Punishments

After thus completing his argument for the main thesis of the dialogue and showing justice to be an intrinsic good, Socrates goes on to remind us that justice is also attended by the many extrinsic rewards with which it is traditionally associated (612c). The just man, for example, garners a better reputation among gods and men. Socrates argues that the gods, being gods, will notice who is just and who isn’t (612e). And, since they are gods, they will love the just, hate the unjust, and act in the world accordingly (612e). Socrates explains:

“And won’t we also agree that everything that comes to someone who is loved by the gods, insofar as it comes from the gods themselves, is the best possible, unless it is the inevitable punishment for some mistake made in a former life? …. Then we must suppose that the same is true of the just person who falls into poverty or disease or some other apparent evil, namely, that this will end well for him, either during this lifetime or afterwards, for the gods never neglect anyone who eagerly wishes to become just and who makes himself as much like a god as a human can by adopting a virtuous way of life” (613a).

And the same holds true for their reputation among men. Socrates likens the situation to a marathon in which the unjust man begins by sprinting. He appears to be in the lead at first, but, by the end, he fails miserably. The just man, in contrast, will enjoy “a good reputation” after he has fought the good fight and finished the race. In fact, Socrates argues that just men generally obtain exactly what was earlier attributed to the secretly unjust. He observes:

“Then will you allow me to say all the things about them that you yourself said about unjust people? I’ll say that it is just people who, when they’re old enough, rule in their own cities (if they happen to want ruling office) and that it is they who marry whomever they want and give their children in marriage to whomever they want. Indeed, all the things that you said about unjust people I now say about just ones. As for unjust people, the majority of them, even if they escape detection when they’re young, are caught by the end of the race and are ridiculed. And by the time they get old, they become wretched, for they are insulted by foreigners and citizens, beaten with whips, and made to suffer those punishments, such as racking and burning, which you rightly described as crude” (613d-e).

And these are the merely external rewards and punishments that men garner in this life. If we expand our view to consequences after death, the contrast becomes even more stark.

Rewards and Punishments After Death

Plato believes in the immortality of the soul, so the consequences of justice and injustice will abide even after the death of the body. Plato argues for the soul’s immortality in more detail in the Phaedo, which recounts Socrates last dialogue before his execution, but, for the purposes of his more limited argument here in the Republic, he simply points out that, since injustice, the natural evil of the soul, is insufficient to destroy it, it is unlikely that anything will. He stipulates that “the bad is what destroys and corrupts, and the good is what preserves and benefits” (608e). And just as individual natures have natural goods towards which they strive, they also have natural evils that beset them. “For example, ophthalmia for the eyes, sickness for the whole body, blight for grain, rot for wood, rust for iron or bronze” (608e). Once these natural evils attach themselves to an entity for which they are the natural evil, they “make the whole thing in question bad” and “disintegrate and destroy it wholly” (609a). And, as argued earlier, “injustice, licentiousness, cowardice, and lack of learning” are the natural evils of the soul. Yet, these evils are unable to destroy it. If they were, the tyrant would cease to exist the moment he became a tyrant (610e-611a). So, people must weigh their decisions in light of the fact that their lives will continue beyond bodily death. And, Socrates contends,

“The prizes, wages, and gifts that a just person receives from gods and humans while he is alive” are “nothing in either number or size compared to those that await just and unjust people after death. And these things must also be heard, if both are to receive in full what they are owed by the argument” (613e-614a).

Plato thus closes the Republic with his famous myth of Er in which he adumbrates the consequences of justice and injustice after death. According to Socrates, Er was a brave Pamphylian man who died in a war (614b). His body was collected for burial, but, twelve days later, he came back to life during his funeral and testified to what he saw in “the world beyond.” (614c). Er claims that souls are gathered and face judgment after death. The unjust are commanded to descend through a door on the left where they will be punished for their crimes. And the just are told to ascend upward through a door on the right where they will be rewarded for their virtuous deeds. They remain in these upper and lower worlds for a thousand years and receive a tenfold recompense for their actions. Socrates explains:

“If, for example, some of them had caused many deaths by betraying cities or armies and reducing them to slavery or by participating in other wrongdoing, they had to suffer ten times the pain they had caused to each individual. But if they had done good deeds and had become just and pious, they were rewarded according to the same scale” (615b).

In this manner, the just are rewarded and the unjust are punished. In addition to this general principle of tenfold recompense, Socrates notes that Er’s story relates an additional consequence for the tyrannical life and an additional benefit for the philosophical one. For Er claims that after the one thousand year cycle is completed, souls return from the upper and lower realms to once more reincarnate on earth. However, great tyrants prove to be an exception to this rule, since truly tyrannical souls are not allowed to escape their punishment, but are instead further tortured and thrown into Tartarus. Socrates recounts Er’s story as follows:

“For example, he said he was there when someone asked another where the great Ardiaeus was. (This Ardiaeus was said to have been a tyrant in some city in Pamphylia a thousand years before and to have killed his aged father and older brother and committed many other impious deeds as well.) And he said that the one who was asked responded: ‘He hasn’t arrived here yet and never will, for this too was one of the terrible sights we saw. When we came near the opening on our way out, after all our sufferings were over, we suddenly saw him together with some others, pretty well all of whom were tyrants (although there were also some private individuals among them who had committed great crimes). They thought that they were ready to go up, but the opening wouldn’t let them through, for it roared whenever one of these incurably wicked people or anyone else who hadn’t paid sufficient penalty tried to go up. And there were savage men, all fiery to look at, who were standing by, and when they heard the roar, they grabbed some of these criminals and led them away, but they bound the feet, hands, and head of Ardiaeus and the others, threw them down, and flayed them. Then they dragged them out of the way, lacerating them on thorn bushes, and telling every passer-by that they were to be thrown into Tartarus, and explaining why they were being treated this way.’ And he said that of their many fears the greatest each one of them had was that the roar would be heard as he came up and that everyone was immensely relieved when silence greeted him. Such, then, were the penalties and punishments and the rewards corresponding to them” (615d-616a).

Thus, the man who chooses a tyrannical path takes upon himself the additional risk of eternal damnation. Not only does the tyrannical life have this additional consequence, but, Socrates promises, the philosophical life also brings with it an additional benefit. For, according to Er, souls choose the type of life they will lead in their next incarnation. The unfolding of one’s next life is thus not a matter of fate or necessity, but is freely chosen by the individual and, thus, something for which they alone are responsible. Er, recounts the goddess’s message as follows:

“Here is the message of Lachesis, the maiden daughter of Necessity: ‘Ephemeral souls, this is the beginning of another cycle that will end in death. Your daemon or guardian spirit will not be assigned to you by lot; you will choose him…. Virtue knows no master; each will possess it to a greater or less degree, depending on whether he values or disdains it. The responsibility lies with the one who makes the choice; the god has none” (617e).

Through this act of autonomous self-determination, the soul must choose from among various models of life, both human and animal. It is at this point of absolute self-determination and responsibility that Socrates claims the soul faces its greatest danger. For it is possible to choose wrongly. Many people see the external trappings of the tyrannical life and hastily select it, only to later lament when they see the true nature of the character they have chosen (619c). In fact, Socrates claims that there is a general trade off in which many from the upper world, who got there not by reflection, but by adopting a good character unthinkingly on account of living in a good city, are careless and choose a morally corrupt life, and many from the lower world, coming directly from their sufferings, realize the hefty consequences of their choice, and take time to examine the lives before them more closely (619d).

The philosopher, however, has a decisive advantage here, since he will be uniquely situated to reason about which characteristics of a life are indicative of virtue and which of vice, and thus ensure that “his journey from here to there and back again won’t be along the rough underground path, but along the smooth heavenly one” (619e). Socrates thus encourages Glaucon, and each of us, that:

“Each of us must neglect all other subjects and be most concerned to seek out and learn those that will enable him to distinguish the good life from the bad and always to make the best choice possible in every situation. …. And from all this he will be able, by considering the nature of the soul, to reason out which life is better and which worse and to choose accordingly, calling a life worse if it leads the soul to become more unjust, better if it leads the soul to become more just, and ignoring everything else: We have seen that this is the best way to choose, whether in life or in death. Hence, we must go down to Hades holding with adamantine determination to the belief that this is so, lest we be dazzled there by wealth and other such evils, rush into a tyranny or some other similar course of action, do irreparable evils, and suffer even worse ones. And we must always know how to choose the mean in such lives and how to avoid either of the extremes, as far as possible, both in this life and in all those beyond it. This is the way that a human being becomes happiest” (618c-619a).

Thus Plato, through the voice of Socrates concludes the Republic as follows:

“But if we are persuaded by me, we’ll believe that the soul is immortal and able to endure every evil and every good, and we’ll always hold to the upward path, practicing justice with reason in every way. That way we’ll be friends both to ourselves and to the gods while we remain here on earth and afterwards—like victors in the games who go around collecting their prizes—we’ll receive our rewards. Hence, both in this life and on the thousand year journey we’ve described, we’ll do well and be happy” (621c-d).

Conclusion

And so concludes our journey through Plato’s Republic. I’d like to thank you for your time and attention as we’ve walked through this epoch-making work together. My hope is that, by taking the time to think through Plato’s ideas, you will have come to see yourself and that for which you strive a little more clearly. For, as Plato notes, it can be easy to become so lost in the mire of our polluted age that we can no longer recognize our true nature, likening the situation to that of the sea god Glaucus who is rendered unrecognizable by the sea grime in which he is encrusted.

“Some of the original parts have been broken off, others have been crushed, and his whole body has been maimed by the waves and by the shells, seaweeds, and stones that have attached themselves to him, so that he looks more like a wild animal than his natural self (611d).”

Our souls, likewise, are beset by many evils. Thus, to see our nature rightly, we must look outward and upward to that for which we yearn. Or, in Plato’s words, the soul must look:

“To its philosophy, or love of wisdom. We must recognize what it grasps and longs to have intercourse with, because it is akin to the divine and immortal and what always is, and we must realize what it would become if it followed this longing with its whole being, and if the resulting effort lifted it out of the sea in which it now dwells, and if the many stones and shells (those which have grown all over it in a wild, earthy, and stony profusion because it feasts at those so-called happy feastings on earth) were hammered off it. Then we’d see what its true nature is” (611e-612a).

If, in our time together, you have caught a glimpse of something in yourself that longs for the eternal, my hope and prayer is that you will follow that yearning lightward, past the realm of shadows and even the terrestrial sun, into the radiance of deep heaven, and, ultimately, to the true noetic light the Form of the Good itself and its promise of a yet deeper magic.

[The image used in the thumbnail of this essay is Titian’s “Sacred and Profane Love.” It is in the public domain and can be found here: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tiziano_-Amor_Sacro_y_Amor_Profano(Galer%C3%ADa_Borghese,_Roma,_1514).jpg]