Plato’s Republic Book VIII: On the Fall of Civilizations

In this essay, I explore Book 8 of The Republic and set forth Plato’s theory of cultural decline.

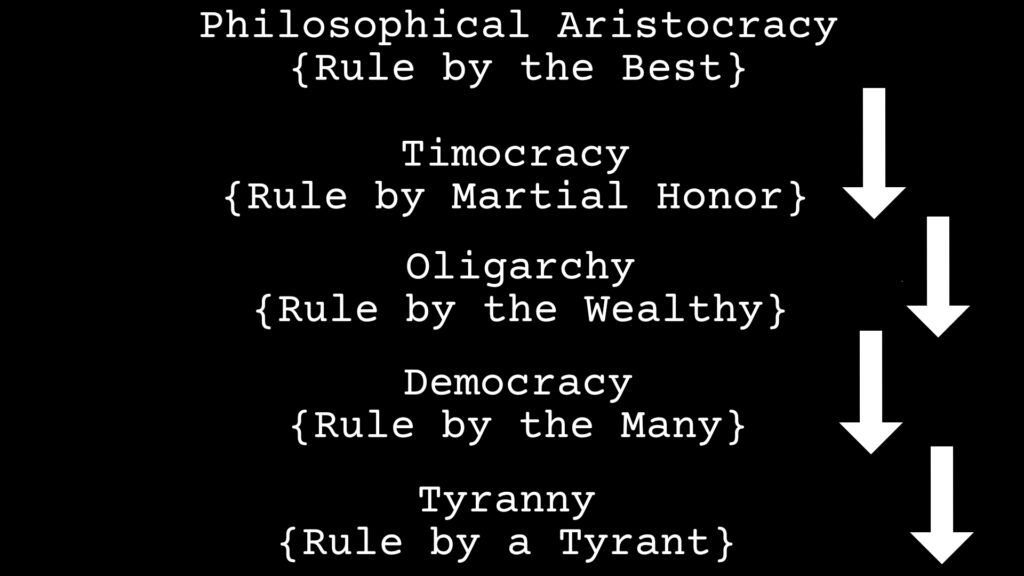

In Book 8 of The Republic, Plato returns to the theme of how his ideal city degenerates into various lesser forms of government: Philosophical aristocracy falling to timocracy, timocracy to oligarchy, oligarchy to democracy, and finally democracy to tyranny.

Since Plato has already described his ideal city in detail earlier—a city ruled by sages who grasp eternal reality, and are followed by auxiliaries who defend the city from invaders, and by productive citizens who cultivate the material life of the city. What remains to be done, then, is to describe the basic kinds of degraded city and to show how higher civilizations degenerate into lower ones.

Such an account clashes with the contemporary myth of progress. We, in the contemporary Western world are conditioned think of ourselves as the zenith of human civilization. Mankind began as brutes and slowly developed culture and technology, advancing step by step to our own age, where the answers to all life’s questions, it is said, lay literally at one’s fingertips. What once demanded long periods of study and observation, can now be googled in an instant from one’s smartphone. This grandiose self-conception is the polar opposite of previous eras. For, while we see ourselves as standing at the heights of human culture, looking on those behind us with a mixture of pity and disgust, previous eras could only see the heights from which they had fallen, heights to which they looked back with reverence and awe. Behind us lay the golden age, to which ours stands as an age of iron (or perhaps iron and clay). Plato’s account of the fall of culture must be understood within this more traditional conception.

The Fall of Cities

Socrates begins by noting that the fall of the ideal city is inevitable, since everything in the realm of becoming is subject to death. He observes,

“It is hard for a city composed in this way [i.e. the ideal city] to change, but everything that comes into being must decay. Not even a constitution such as this will last forever. It, too, must face dissolution” (546a).

He argues that the proximate cause of the city’s dissolution will be “a civil war breaking out within the ruling group itself”, for “if this group—however small it is—remains of one mind, the constitution cannot be changed” (545c). Such a civil war will be possible when the rulers eventually fail to correlate human generation with the ideal numbers governing it. He observes:

“Now, the people you have educated to be leaders in your city, even though they are wise, still won’t, through calculation together with sense perception, hit upon the fertility and barrenness of the human species, but it will escape them, and so they will at some time beget children when they ought not to do so. For the birth of a divine creature, there is a cycle comprehended by a perfect number” (546b).

Because they fail to correlate the city’s reproductive cycle with the ideal electional times governed by Pythagorean numerology, some children will be born who are “neither good natured nor fortunate” (546c).[1] The next generation of guardians will thus be of inferior quality to those who preceded them. Once the new generation begins to take charge of the city, they will neglect the muses, having “less consideration for music and poetry than they ought” and, consequently, “will become less well educated in music and poetry” (546d). Because of their gracelessness and lack of harmony, they will fail to adequately distinguish the various natures of the people, thereby breaking down the distinctions between the various classes. For example, they will assign those who should be soldiers to the work of philosophical study, those who should work the land to warfare, and those who should be contemplating the eternal to husbandry. Socrates observes, “the intermixing of iron with silver and bronze with gold that results will engender lack of likeness and unharmonious inequality, and these always breed war and hostility wherever they arise. Civil war, we declare, is always and everywhere ‘of this lineage.’” (547a). Timocracy is the result of this war.

Timocracy

There are two factions in this first civil war in the city. On the one hand, the baser natures of iron and bronze want to replace the good toward which the city strives. Instead of the eternal good preached by the philosopher kings, these leaders want to direct the city to money making and the accumulation of material resources for themselves. On the other hand, the nobler natures of gold and silver fight to retain virtue and the eternal philosophical order.

Timocracy, a city focused on martial honor, emerges as a compromise between these two groups. Socrates explains:

“And thus striving and struggling with one another, they compromise on a middle way. They distribute the land and houses as private property, enslave and hold as serfs and servants those whom they previously guarded as free friends and providers of upkeep, and occupy themselves with war and with guarding against those whom they’ve enslaved” (547b).

What used to be communal property is now apportioned and given to the rulers as their own private property. And the productive class that was once the material basis of the city are stripped of their citizenship and enslaved by the ruling class, being reckoned as mere property. In light of this decision to amass wealth for themselves and enslave the rest of the population, martial prowess now becomes the chief value of the ruling class. For, they must now guard both against internal uprisings from the newly created slave class who despise this new arrangement and against external invasion from those who would seek to conquer their lands and carry off their treasures. Additionally, military excellence also allows the rulers to enrich themselves by conquering other cities, stealing their wealth and enslaving their citizenry.

Socrates believes that such a timocracy would stand midway between the ideal aristocracy (a city in which the best rule) and oligarchy (a city in which the wealthy rule) (547d). As in an aristocracy:

“The rulers will be respected; the fighting class will be prevented from taking part in farming, manual labor, or other ways of making money; it will devote itself to physical training and training for war” (547d).

In such a society, there is still some sort of distinction between ruler and ruled that is grounded in some kind of natural excellence. The rulers can fight well, and they devote themselves to this craft. There are clear standards that separate the good soldier from the bad, and the honorable from the dishonorable. But, as in an oligarchy, a timocracy:

“will be afraid to appoint wise people as rulers, on the grounds that they are no longer simple and earnest but mixed, and will incline towards spirited and simpler people, who are more naturally suited for war than peace; it will value the tricks and stratagems of war and spend all its time making war” (547e-548a).

Because such a society has neglected the muses and turned its back on philosophical training, its so called intellectuals are no longer trustworthy, and cannot be appointed to rule. As a result, the rulers will be selected from those who formerly would have constituted the auxiliary class. They will be full of spirit and live for war and conquest.

Thus we have a timocracy, a society which organized around martial honor and virtue as its highest good. Its leaders will love victory and honor above all (548c). Yet, because they have turned away from philosophy and discussion, and been educated in force rather than persuasion, they will not have the insight or fortitude to shun material wealth. They will love it, but do so secretly (548b-c). “They will possess private treasuries and storehouses, where they can keep it hidden, and have houses to enclose them, like private nests, where they can spend lavishly either on women or on anyone they might wish” (548a). They will be at once hoarders and spendthrifts. In light of their love of money, they will hoard their own secret funds, while spending other people’s money with abandon (548b).

Oligarchy

Whereas Plato presents the fall from ideal aristocracy to timocracy as having to do with the inherent weakness of the world of becoming, with even the best of sages unable to adequately correlate the life of the city with the proper electional times dictated by Pythagorean numerology, the subsequent stages of cultural deterioration are generated by their false conceptions of the good (562b). Each degenerate city thus contains the seeds of its own destruction within itself through its own faulty conception of the good.

Socrates begins by noting how the timocratic city degenerates into an oligarchy, a “constitution based on a property assessment, in which the rich rule, and the poor man has no share in ruling” (550d). We have already noted that, without the guidance of philosophy, the ruling class developed a secret love for wealth. The fall from timocracy to oligarchy occurs when this covert love is rendered overt and celebrated. Presumably, pursuing the one sided good of military prowess devolves into the pursuit of money, because military virtues are not self-sufficient. One must ask, like Achilles in the Iliad, why he should continually stake his life in battle. What is he fighting for and is it worth it? In the old philosophical aristocracy, one could say that he fights for his city, his family, his fellow citizens, and ultimately for the eternal Good towards which his city strives. But there are no sages in a timocracy, and man can no longer raise his eyes to the eternal. The most ready answer, then, to the warrior’s question, is that he fights for spoils, to enlarge his material resources. He had already secretly loved money, and now he no longer has any reason to hide it. Socrates explains, “first, they find ways of spending money for themselves, then they stretch the laws relating to this, then they and their wives disobey the laws altogether” (550d).

Once a few prominent leaders do this, the rest soon follow, until the majority behave this way (550e). Becoming accustomed to flaunting their wealth, they decide that they ought to be able to engage in activities to acquire more of it, activities of a non-martial nature. “From there they proceed further into money making, and the more they value it, the less they value virtue.” (550e). And so, as the accumulation of wealth for the ruling class is exalted as the chief end of the city, the other virtues are debased and neglected. So, “in the end, victory-loving and honor loving men become lovers of making money, and money-lovers. And they praise and admire wealthy people and appoint them as rulers, while they dishonor poor ones” (551a).

And these money lovers will pass laws to make material wealth a requirement for rule, proclaiming that “those whose property doesn’t reach the stated amount aren’t qualified to rule” (551b). Socrates claims that “they will put this through by force of arms, or else, before it comes to that, they terrorize the people and establish their constitution that way” (551b).

Socrates argues that this form of government will give rise to a multitude of vices. He first points out the inherent foolishness of the arrangement. Returning to the nautical metaphor used earlier, he asks us to imagine what would happen if ships’ captains were selected on the basis of their personal assets rather than on their knowledge of sailing. One would board such a ship only at great peril. And he argues that the same holds true for states that select their rulers on the basis of their material wealth rather than on their wisdom or virtue (551c). For these rulers are selected without any regard for what right rule ought to consist in.

Second, in an oligarchy, there is, in truth, no longer one city. There are two cities—the poor and the rich– who live within the same geographical region and who are constantly “plotting against one another” (551d). The poor seek to overthrow the rich rulers and enjoy their goods for themselves, and the rich seek to prevent this from happening and to further exploit the poor.

Third, because they have given up martial virtue and have devoted themselves to other, more profitable, forms of money making, the ruling class in an oligarchy is no longer capable of waging war. There are only a few of them, and they no longer have the spirit or physical strength to be victorious in combat. Thus, to defend the city, i.e. to defend their own wealth, they must either arm the people or hire foreign mercenaries. But oligarchs are unlikely to do either of these things, since (i) they have more reason to fear the people they have oppressed than the invading enemy and (ii) the are reluctant to spend the huge sums needed to hire foreign mercenaries (551e).

Fourth, an oligarchy would be the first constitution to enshrine injustice. People would be expected to meddle in multiple affairs at once, and thus do all of them poorly. The rulers, for example, would attempt not only to rule, but, since they see opportunities to further enrich themselves, they also would try to manage agriculture, military campaigns, artistic productions, etc.

Finally, and most grievously, Socrates argues that the oligarchic constitution would be the first to introduce “the greatest of all evils into the city” (552a), since it is the first to introduce an absolutely impoverished class. Socrates observes:

“Allowing someone to sell all his possessions and someone else to buy them and then allowing the one who has sold them to go on living in the city, while belonging to none of its parts, for he’s neither a money-maker, a craftsman, a member of the calvary, or a hoplite, but a poor person without means…. This sort of thing is not forbidden in oligarchies. If it were, some of their citizens wouldn’t be excessively rich, while others are totally impoverished” (552a-b).

He likens such people to drones in a beehive, claiming that some have stingers while other don’t. The stingless ones are beggars, but the ones with stingers are evildoers: thieves, pickpockets, and temple robbers (552d). Socrates maintains that both will be found in oligarchic cities. You will find beggars, since “almost everyone except the rulers is a beggar there” (552d), and “many evildoers with stings, whom the rulers carefully keep in check by force” (552e).

Democracy

As timocracy’s false conception of the good caused it to succumb to oligarchy, so too does oligarchy’s identification of the good with material wealth lead to its undoing. Oligarchy falls to democracy in light of “its insatiable desire to attain what it has set before itself as the good, namely, the need to become as rich as possible” (555b). Given the injunction to become as wealthy as possible, ruling families will cannibalize each other to gain their wealth. Socrates observes:

“Since those who rule in the city do so because they own a lot, I suppose they’re unwilling to enact laws to prevent young people who’ve had no discipline from spending and wasting their wealth, so that by making loans to them, secured by the young people’s property, and then calling those loans in, they themselves become even richer” (555c).

By preying on the extravagant desires of the youth, desires inflamed and cultivated in an oligarchy, a few families can consolidate power through moneylending. They will lend money to fund degenerate lifestyles, and then call in those loans to appropriate the property of other ruling families. The number of ruling families will thus become fewer and fewer as their wealth continues to increase. As a result, there will now be a large portion of the impoverished “drone” population who were once rulers themselves, and who harbor a deep resentment for those who have reduced them to poverty. Socrates observes:

“And these people sit idle in the city, I suppose, with their stings and weapons—some in debt, some disenfranchised, some both—hating those who’ve acquired their property, plotting against them and others, and longing for a revolution” (555d).

And, willfully ignorant of the danger before them, the wealthy continue with their usury:

“The money-makers, on the other hand, with their eyes on the ground, pretend not to see these people, and by lending money they disable any of the remainder who resist, exact as interest many times the principal sum, and so create a considerable number of drones and beggars in the city” (555e).

And, and as they continue to increase the number of their enemies, the rulers also weaken themselves and their children through their lazy and luxurious lifestyles. Socrates observes,

“But as for themselves and their children, don’t they make their young fond of luxury, incapable of effort either mental or physical, too soft to stand up to pleasures or pains, and idle besides?…And don’t they themselves neglect everything except making money, caring no more for virtue than the poor do?” (556c).

Because the rulers no longer have to do anything but bleed the wealth of others through usury, they occupy themselves with spending their wealth on luxuries and fail to actively engage with life. Thus, in the late stages of an oligarchy, the ruling class will be small, useless, and surrounded by a citizenry that despises it. Furthermore, on those occasions when rich and poor are forced to work together, e.g. at a festival or in a military campaign, the poor will observe how worthless and pathetic their rulers actually are. Socrates notes,

“But when rulers and subjects in this condition meet on a journey or some other common undertaking—it might be a festival, an embassy, or a campaign, or they might be shipmates or fellow soldiers—and see one another in danger, in these circumstances are the poor in any way despised by the rich? Or rather isn’t it often the case that a poor man, lean and suntanned, stands in battle next to a rich man, reared in the shade and carrying a lot of excess flesh, and sees him panting and at a loss? And don’t you think that he’d consider that it’s through the cowardice of the poor that such people are rich and that the poor man would say to another when they met in private: ‘These people are at our mercy; they’re good for nothing’” (556d-e).

Not only will the people resent their leaders for exploiting them, but they will see that the only reason they continue to be so exploited is that they have failed to push back. For the rulers themselves are infirm and incompetent, incapable of defeating the people were they were they to be roused against them.

Civil war would be thus immanent, all that would be needed was for an incident to rally the people to action. Socrates explains:

“Then, as a sick body needs only a slight shock from outside to become ill and is sometimes at civil war with itself even without this, so a city in the same condition needs only a small pretext—such as one side bringing in allies from an oligarchy or some other from a democracy—to fall ill and to fight with itself and is sometimes in a state of civil war even without any external influence” (556e).

When this war happens and the poor win, the resulting state is democracy.

“Democracy comes about when the poor are victorious, killing some of their opponents and expelling others, and giving the rest an equal share in ruling under the constitution, and for the most part assigning people to positions of rule by lot” (557a).

Because wealth proved to be an insufficient ground for rulership, the people decide to forgo all conditions of rule, and simply assign it randomly according to the whims of the people. Ultimately, the constitution they enact is one of license—one in which people are free to do whatever they want (557b). In such a city, “each of them will arrange his own life in whatever manner pleases him” (557b). So, in a democracy, one will find a variety of people, and it can seem like the best of constitutions because it seems so colorful (557c).

In fact, Socrates argues, the democratic constitution isn’t one constitution at all, but a conglomeration of all types of constititions, since, in its anarchy, it allows for all forms of life.” (557d). He notes:

“In this city, there is no requirement to rule, even if you’re capable of it, or again to be ruled if you don’t want to be, or to be at war when the others are, or at peace unless you happen to want it. And there is no requirement in the least that you not serve in public office as a juror, if you happen to want to serve, even if there is a law forbidding you to do so. Isn’t that a divine and pleasant life, while it lasts? (557e-558).”

Democracy does not discriminate on the basis of character as the ideal city did, but now chooses its leaders only on the basis of whether they please the majority.

“And what of the city’s tolerance? Isn’t it so completely lacking in small-mindedness that it utterly despises the things we took so seriously when we were founding our city, namely, that unless someone had transcendent natural gifts, he’d never become good unless he played the right games and followed a fine way of life from early childhood? Isn’t it magnificent the way it tramples all this underfoot, by giving no thought to what someone was doing before he entered public life and by honoring him if only he tells them that he wishes the majority well?” (558b).

Democracies are more tolerant than other constitutions because they abandon all objective criteria for rulership. Unlike the philosophical aristorcracy, rulers are no longer chosen on the basis of their spiritual insight. Unlike the timocracy, they are no longer chosen on the basis of their courage or physical strength. And, unlike the oligarchy, they are no longer chosen even on the basis of wealth. Rather, in a democracy, leaders are selected not on the basis of any qualifications they might have, but on the basis of whether they can make the majority of people feel good about them. In this manner, Socrates concludes that democracy “would seem to be a pleasant constitution, which lacks rulers but not variety and which distributes a sort of equality to both equals and unequals alike.” (558c). Anyone can do whatever they want, regardless of whether it is good and whether they are suited for it. While it lasts this can seem like a pleasant state, but, Socrates argues, this anarchic constitution inevitably collapses into tyranny.

Tyranny

As with the previous constitutions, democracy’s faulty conception of the good leads to its own downfall. Its “insatiable desire for what it defines as the good”, in this case absolute freedom, is “also what destroys it” (562b). Democracy thus results in tyranny, just as it itself was the result of oligarchy. For its one sided focus on freedom leads to its opposite, dictatorship. Socrates asks “doesn’t the insatiable desire for freedom and the neglect of other things change this constitution and put it in need of a dictatorship?” (562c).

In a democracy, rulers are praised who behave like subjects, and subjects who behave like rulers (562e). All distinctions are obliterated in its anarchy (562e). Socrates explains:

“A father accustoms himself to behave like a child and fear his sons, while the son behaves like a father, feeling neither shame nor fear in front of his parents, in order to be free. A resident alien or a foreign visitor is made equal to a citizen, and he is their equal…. A teacher in such a community is afraid of his students and flatters them, while the students despise their teachers or tutors. And, in general, the young imitate their elders and compete with them in word and deed, while the old stoop to the level of the young and are full of play and pleasantry, imitating the young for fear of appearing disagreeable and authoritarian (563a).”

In such a society, there is no longer a distinction between parent and child, citizen and alien, student and teacher, and the customs and rituals anchored in such distinctions dissolve along with them. Indeed, any concept of law proves to be intolerable in a democracy. Socrates observes:

“To sum up: Do you notice how all these things together make the citizens’ souls so sensitive that, if anyone even puts upon himself the least degree of slavery, they become angry and cannot endure it. And in the end, as you know, they take no notice of the laws, whether written or unwritten in order to avoid having any master at all” (563d).

Tyranny soon develops from such lawlessness, “the most severe and cruel slavery” emerging “from the utmost freedom” (564a). Socrates notes that there are three types of citizen in a democracy. The first, and most dominant, are what he earlier called the drones. They are the idlers who practice no craft and have no wealth, contributing nothing to the city. These are the ones who will be most involved in democratic politics. Socrates observes:

“Its fiercest members do all the talking and acting, while the rest settle near the speaker’s platform and buzz and refuse to tolerate the opposition of another speaker, so that, under a democratic constitution, with a few exceptions I referred to before, this class manages everything” (564d).

The second class of citizen, Socrates calls drone fodder. They are the most organized and tend to be the wealthiest. “They would provide the most honey for the drones and the honey is the most extractable by them” (564e).

And, finally, there is the productive class who works with their hands, practicing agriculture and various crafts. This class is the most numerous, and, when gathered together, are the most powerful in a democracy. However, they are so busy working that they will only be gathered together if they can get a reward. “They aren’t willing to assemble often unless they get a share of the honey” (565a).

Given this threefold division of society, the following scenario unfolds. The drones target someone of means in order to extract their wealth. To get a majority, they must promise something to the workers. So they redistribute the wealthy person’s resources, so as to give a little to the workers, while keeping the majority for themselves. In this manner, the drones play the other two segments of society against each other. In order to justify seizing their wealth, the drones accuse the affluent of secretly wishing to be oligarchs. And, given such continued assaults, many of the affluent do end up embracing oligarchic ideals as a means of self-defense. But Socrates observes that neither of the affluent nor the workers does so willingly, but only because they are goaded on by the drones:

“But neither group does these things willingly. Rather the people act as they do because they are ignorant and are deceived by the drones, and the rich act as they do because they are driven to it by the stinging of those same drones” (565c).

It is this perpetual conflict that sets the stage for the emergence of a tyrant. In these battles, the people will often pick a champion drone to carry out their interests (565c). Such a champion becomes a tyrant once he tastes the blood of his fellow citizens, for example, once he sees that he can bring people up on false charges, execute them, and then seize their property. Socrates likens the scenario to a myth of the temple of Lycean Zeus in which “anyone who tastes one piece of human innards that’s chopped up with those of the sacrificial victims must inevitably become a wolf” (565e). Similarly, anyone who has tasted the blood of his fellow citizens, will become a tyrant. Socrates explains:

“Then doesn’t the same happen with a leader of the people who dominates a docile mob and doesn’t restrain himself from spilling kindred blood? He brings someone to trial on false charges and murders him (as tyrants so often do), and, by thus blotting out a human life, his impious tongue and lips taste kindred citizen blood. He banishes some, kills others, and drops hints to the people about cancellation of debts and redistribution of land. And because of these things, isn’t a man like that inevitably fated either to be killed by his enemies or to be transformed from a man into a wolf by becoming a tyrant” (565e-566a).

In instigating civil wars against the wealthy, he will earn many enemies for himself. And, claiming to be the champion of the people, he will petition them for a private bodyguard to ensure his safety. This, claims Socrates, is “the famous request of the tyrant” (566b). The people give it to him, “because they are afraid for his safety but aren’t worried at all about their own” (566b).

At the beginning of his reign, the tyrant will appear to be gentle and benevolent. Socrates observes:

“During the first days of his reign and for some time after, won’t he smile in welcome at anyone he meets, saying that he’s no tyrant, making all sorts of promises both in public and in private, freeing the people from debt, redistributing the land to them and his followers, and pretending to be gracious and gentle to all?” (566e).

His next step will be to once again stir up war to solidify his position (566e). For a state of perpetual war will reinforce his power in three ways. First, it will make the people continue to feel the need for his leadership (566e). Fearing that, without him, they would be crushed by the enemy. Second, the people will soon be impoverished from the war taxes levied on them, and so will occupy themselves with survival, and thus not be in a position to plot against him (567a). And finally, the war will give the tyrant plausible deniability in eliminating his enemies. He will simply deliver them over to the enemy, and they will do his dirty work (567a).

This situation will cause him to be increasingly hated by the citizens, and the brave and resourceful ones who helped put him in power will begin to plot against him (567b). He will thus have to eliminate them, being left with “neither friend nor enemy of any worth” (567b), because he has purged the city of everyone “brave, large minded, knowledgeable, or rich” (567c). Unlike doctors who purge out the worse elements of the body and leave the better, the tyrant purges the best and leaves the worst (567c).

Because everyone hates him, he will need a larger and more loyal bodyguard. He will not be able to find them among the citizens, so he’ll hire foreign drones and free the slaves and take them on as his bodyguards (567e). “These companions and new citizens admire and associate with him, while the decent people hate and avoid him.” (568a).

To pay for these foreign mercenaries he’ll exhaust the sacred treasures and tax the people into poverty. But eventually even these funds will dry up. At that point, he’ll begin to bleed his father’s estate. When the people complain about this outrage, pointing out that they didn’t put him in charge in order to be the slaves of slaves, and attempt to remove him from power, they will see what kind of monster they have created (569a).

“By trying to avoid the frying pan of enslavement to free men, the people have fallen into the fire of having slaves as their masters, and that in the place of the great but inappropriate freedom they enjoyed under democracy, they have put upon themselves the harshest and most bitter slavery to slaves” (569c).

And so, the fall of the city is complete. Each constitution, by pursuing a false good, has been led progressively into greater evils, until finally completely collapsing in tyranny. It is interesting to compare Plato’s dialectical account with later those of the later philosophical tradition. For example, Hegel believed, like Plato, that societies were ultimately undone by their own one-sided conceptions of the good. But, unlike Plato, being a modern and Christian, Hegel considered this sequence to be progressive, likening it the stations of the cross, a road of suffering which ultimately led to freedom. This was not the case for Plato. For him, the unfolding of the realm of becoming was not the advance of freedom, but the steady march to tyranny. Freedom, for Plato, is not to be found in the dialectical unfolding of the lesser goods of the world of becoming, but in the soul’s ascent to the eternal, and, perhaps, in the turning of fortune’s wheel back to its starting point and reinstituting the ideal state.

[The image used in the thumbnail of this post is “The Confusion of Tongues” by Gustave Dore and is in the public domain. It can be found here: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Confusion_of_Tongues.png]

[1] He explains this perfect electional number as follows: “For a human being, it is the first number in which are fond root and square increases, comprehending three lengths and four terms, of elements that make things like and unlike, that cause them to increase and decrease, and that render all things mutually agreeable and rational in relation to one another. Of these elements, four and three, married with five, give two harmonies when thrice increased. One of them is a square, so many times a hundred. The other is of equal length one way but oblong. One of its sides is one hundred squares of the rational diameter of five diminished by one each or one hundred squares of the irrational diameter diminished by two each. The other side is a hundred cubes of three. This whole geometrical number controls better and worse births.” (546b-c).