Manilius and the Planetary Joys: An Alternative Pythagorean Account of the Places in Hellenistic Astrology

Marcus Manilius’s Astronomica is one of our oldest and most detailed historical sources for how ancient astrologers conceptualized the twelve places. Manilius is believed to have composed this work in the early first century, probably around 14 A.D.1 In contrast, Valens, whom astrologer Chris Brennan acclaims as “the single most important surviving source for studying the Hellenistic astrological tradition”2 composed his Anthologies about one hundred and fifty years later, 3 and Rhetorius wrote his Compendium, one of the only other extant texts that seeks to give an explicit argument for the assignments of planets to places, about six or seven hundred years after Manilius.4 Yet, despite its antiquity and philosophical depth, Manilius’s work is often dismissed by those seeking to reconstruct the practice of Hellenistic Astrology.5 Robert Schmidt, for example, rejects his work and condemns Manilius’s “characterizations of the houses” as “so sketchy” and “so aberrant” that one should have “little confidence in them.”6

I contend that such a peremptory dismissal of Manilius’s work is misguided and that an understanding of the Astronomica is crucial for reconstructing the philosophical framework for the practice of Hellenistic Astrology. Specifically, I will argue in this essay that Manilius’s alternative conceptualization of the planetary joys represents a genuinely alternative tradition. His schematization of the joys is neither the result of poetic caprice nor literary ineptitude, but is grounded in an alternative Pythagorean tradition of astrology, a tradition worthy of contemporary consideration.

E Pluribus Unum

The claim that there were multiple competing systems of planetary joys should not surprise us. For, though we can identify some common elements of a distinctively Hellenistic Astrology (such as the use of planets, houses, and places), there were nonetheless diverse interpretations of the practice in the ancient world. This fact is clearly attested in our primary sources. For example, Ptolemy famously distinguishes between two systems of terms used in his day, the Egyptian and the Chaldean, and reports coming across a manuscript articulating a third system which he takes to be older and conceptually superior to the other two.7 Likewise, Porphyry, in his Letter to Anebo, reports that there were a variety of conflicting methods for identifying the lord of the nativity and the individual daimon assigned by that lord.8 And, given the canonical status some contemporary astrologers ascribe to Valens, it is important to emphasize his appraisal of the situation:

“I have written for those who wish to learn every systematic procedure. Each of the other astrological compilers has worked out his own complex procedures, but has not published his solutions, since each is secretive and begrudging, and neglected his readers. I, however, have investigated with much toil and long experience, and have published <my system>. This seems to be my greatest achievement, to explicate the ideas of others which have been buried in mystery. I myself could have compiled my many procedures using a fog of words, but I did not want to show myself to be like those babblers. It would be laughable to begin speaking against someone without recognizing first my own faults. Therefore if you find me speaking very often about my generosity and openness, please forgive my words. I suffered much, I endured much toil, I was cheated by many men, and I spent money that seemed to me to be inexhaustible because I was persuaded by mountebanks and greedy men. Nevertheless because of my endurance and my love for systematic knowledge, I outlasted them all. If my readers recognize the accuracy of these systems, they will give us praise with delight. Others, because of their stupidity, will envy and malign us, and they may be exalted by the illumination of mystical and secret things, and they will steal some procedures from my compilation. So on such men I place dire curses, which I think they will suffer.

Let the readers of our collected works, works which explicate all procedures, not say: “This procedure is from the King, this other is from Petosiris, that one is from Critodemus, etc.” Instead let them know that these men propounded their art in an obtuse and recondite fashion, and thereby showed that their science lacked a true foundation. We on the other hand supplied solutions, and not only revived this dying art, but also banked glory for ourselves and initiated other worthy men, attracting them not with the lure of money, but by recognizing them to be scholars and enthusiasts. We too have been controlled by this type of Fate” (Anthologies, VIII.5 trans. Riley).

Valens here acknowledges the existence of many “complex procedures” competing with his own. These alternative procedures are apparently rooted in esoteric traditions, since Valens describes their practitioners as “secretive and begrudging”, burying their ideas “in mystery” and “a fog of words.” Though Valens mocks these rival astrologers as “babblers”, and asserts that the traditions associated with the King (Nechepso), Petosiris, and Critodemus are “obtuse” and “recondite” and thus “lacked a true foundation,”9 we are not compelled to follow his lead.

Indeed, if we are to provide an objective historical account of the astrological practice of Valens’ day, we must reject his approach. For, before we can responsibly argue about which system of Hellenistic astrology is best, we must first establish what the various systems were. And, to do this, we cannot simply pretend that rivals to Valens did not exist, or dismiss them for being “idiosyncratic.”10

The Places and the Planetary Joys.

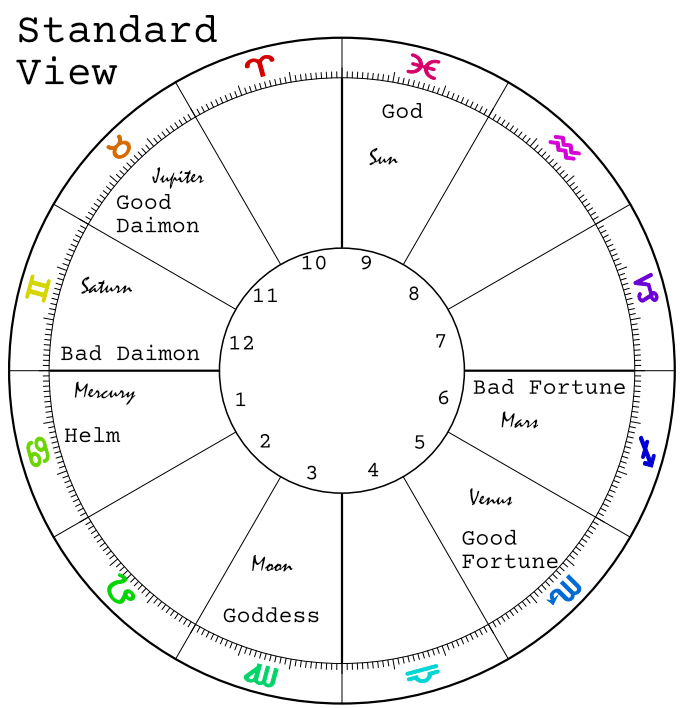

The twelve places, or τόποι, are an essential component of Hellenistic astrology, allowing astrologers to assign various topics to Zodiacal signs. On the standard view, the planetary joys schema is said to be the original source for the topical significations of the places.11 According to this schema, each of the seven traditional planets has a particular place in which it rejoices. Mercury rejoices in the first place (The Helm), the Moon in the third (The Goddess), Venus in the fifth (Good Fortune), Mars in the sixth (Bad Fortune), the Sun in the ninth (The God), Jupiter in the eleventh (Good Daimon), and Saturn in the twelfth (Bad Daimon). This model divides the zodiac is into two hemispheres and associates the upper hemisphere with the realm of Daimon (often translated as “Spirit”) and the lower with the realm of Fortune.

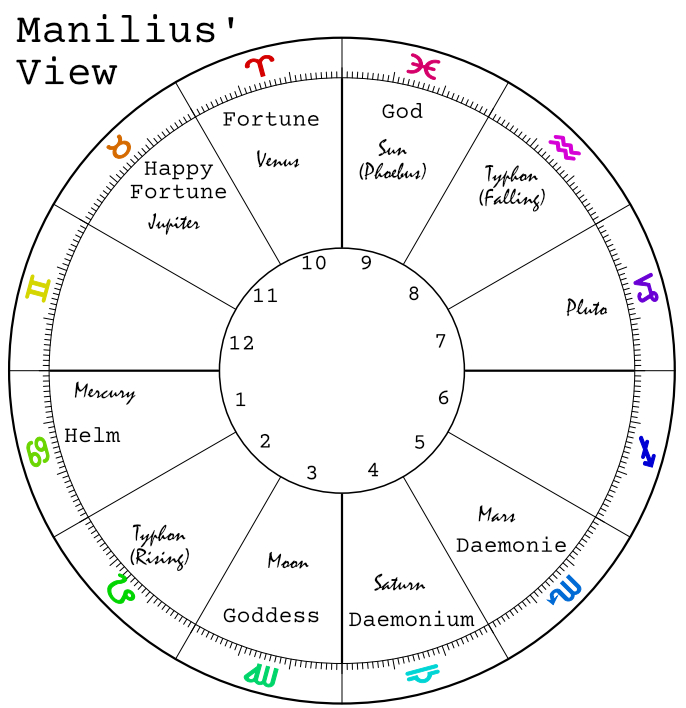

Yet, Manilius provides an alternative model of the planetary joys which is equally capable of accounting for the topical significations of the places. Manilius agrees with the standard model in assigning Mercury to the first, the Moon to the third, the Sun to the ninth,12 and Jupiter to the eleventh.13 But his account diverges from the standard view by assigning Saturn to the fourth place (which he calls Daemonium) rather than the twelfth, Mars to the fifth place (which he calls Daemonie) rather than the sixth, and Venus to the tenth place (which he calls Fortune) rather than the fifth. Additionally, Manilius appeals to gods outside of the traditional seven planets and assigns these gods to three additional places, bringing the number of occupied places to ten. He assigns the second and eighth places to Typhon, associating the former with his rising up in rebellion against Zeus and the latter with divine judgment and his falling to Hades. And Manilius assigns Pluto, lord of the underworld, to the seventh place, the place of setting.

Manilius’s Explanation of the Places

Manilius’s alternative schema of the planetary joys provides a clear, coherent, and elaborate account of the meanings of the twelve places. Let’s examine each of them in turn, starting with the places corresponding to the cardinal points.

The Four Cardinal Points

Manilius begins his account by explaining the significance of the four cardinal points, which, from their fixed positions, “receive in succession the speeding signs” (II.789-90). Unlike other astrologers, Manilius contends that these points are endowed with exceptional power, and, as a result, constitute the most influential parts of a chart. He explains:

“These points are charged with exceptional powers, and the influence they exert on fate is the greatest known to our science, because the celestial circle is totally held in position by them as by eternal supports; did they not receive the circle, sign after sign in succession, flying in its perpetual revolution, and clamp it with fetters at the two sides and the lowest and highest extremities of its compass, heaven would fly apart and its fabric disintegrate and perish” (Astronomica, II.801-807 trans. Goold).

Manilius here claims that, without these orienting points, the motions of the heavens would prove to be incomprehensible. In a view from nowhere, the revolutions of the heavens would be seen as a mere dissociated flow, not a meaningful sequence. A map, for example, no matter how complete and accurate, will prove to be useless if one has no idea where one is. If one cannot anchor a location on the map to a “here” or “there” in one’s perceptual space, the map cannot function as a map. Similarly, the zodiac may perpetually rotate, but if it never intersects with the spatio-temporal horizon of our experience, we will never to able to anchor its motions to our life world. The Zodiac cannot become a natal chart without a horizon by which to fix our indexicals.

And Manilius contends that the power given to the cardinal points extends to their four corresponding temples. He explains:

“In any geniture every sign is affected by the sky’s division into temples; position governs the stars, and endows them with the power to benefit or harm; each of the signs, as it revolves, receives the influence of heaven and to heaven imparts its own. The nature of the position prevails, exercises jurisdiction within its province, and subjects to its own character the signs as they pass by, which now are enriched with distinction of every kind and now bear the penalty of a barren abode” (II.856-863).

Manilius here claims that temples (the places) have power over both planets and signs. They “govern the stars”, and though signs and temples mutually interact, Manilius contends that temples play the dominant role. “The nature of the position prevails”, as temples exercise “jurisdiction” over what occurs within them.

Furthermore, Manilius provides a clear explanation of the powers exerted by each temple. Let’s begin by examining those associated with the cardinal points, a quaternity composed of the crossing of two opposed pairs, the first consisting of the Midheaven and the Imum Coeli and the second of the Ascendant and the Descendant.

The Tenth Place

The highest ranking of these four points, claims Manilius, is the Midheaven. He contends:

“Each cardinal, however, enjoys a different influence; they vary according to their position, and they differ in rank. First place goes to the cardinal which holds sway at the summit of the sky and divides heaven in two with imperceptible meridian; enthroned on high this post is occupied by Glory (truly a fit warden for heaven’s supreme station), so that she may claim all that is pre-eminent, arrogate all distinction, and reign by awarding honors of every kind. Hence comes applause, splendor, and every form of popular favor; hence the power to dispense justice in the courts, to bring the world under the rule of law, to make alliances with foreign nations on one’s own terms, and to win fame relative to one’s station” (II.808-815).

Here Manilius observes that the Midheaven divides the sky above into two parts. In one, planets make their ascent to heaven’s summit, and, in the other, they fall from it. Manilius thus associates this turning point with the Glory which presides over the lofty and noble. He then goes on to identify this goddess of Glory with Venus. He explains:

“But in the citadel of the sky, where the rising curve attains its consummation, and the downward slope makes its beginning, and the summit towers midway between orient and occident and holds the universe poised in its balance, here does the Cytherean claim her abode among the stars, placing in the very face of heaven, as it were, her beauteous features, where with she rules the affairs of men. To the abode is fittingly given the power to govern wedlock, the bridal chamber, and the marriage torch; and this charge suits Venus, the charge of plying her own weapons. Fortune shall be this temples name.”

Here, at the midpoint of the sky, on the peak between rising and falling, reigns Venus, goddess of love and desire. Manilius thus appears to be highlighting the correlation between glory and desire. Why do people seek what is noble and lofty? Because, one might respond, they desire it. But, echoing the dilemma of Euthyphro, we might ask, why do men and women desire such things? To this, it seems, one must confess that if one desires rightly, one desires certain things because they are inherently desirable. One desires lofty things because they are good. So, when approached rightly, Venus thus draws us Godward like Goethe’s eternal feminine. Those drawn on by her charms sing with the mystical chorus:

“All that must disappear/ is but a parable;/ What lay beyond us, here/ all is made visible; / here deeds have understood words they were darkened by; Eternal Womanhood/ Draws us on High” (Goethe, Faust Part II, trans. Luke).14

In this manner, Venus leads “further up and further in” to the eternal.15

But, as we well know, this is not the only way of approaching the goddess, since it is possible to desire merely apparent goods. Hence, the place where worldly glory is consummated is also the beginning of its fall. Manilius thus aptly names this temple Fortune. When we desire merely apparent goods, the yearning for glory becomes the force by which lady fortune spins her wheel, perpetually raising up and casting down the fates of mortals.

The Fourth Place

Opposing the Midheaven is the Imum Coeli, the bottom of the sky, which grounds and supports all the other places. Manilius describes it as follows:

“The next point…bears the world poised on its eternal base; in outward aspect its influence is less, but is greater in utility. It controls the foundations of things and governs wealth; it examines to what extent desires are accomplished by the mining of metal and what gain can issue from a hidden source” (II.820-825).

Because it lies at the very bottom of the sky, it is conceived as its foundation, and thus as governing the foundations of things. Whereas the MC is like the tip a massive tree straining to reach the heavens, the IC is like the hidden roots that bear the entire mighty structure. And, because it lies hidden from our vision, the IC is associated with goods that come to us from occult sources, like gold and silver buried in the earth’s depths. Manilius then dedicates its corresponding temple, the fourth place, to the planet Saturn. He explains:

“Where at the opposite pole [to the MC] the universe subsides, occupying the foundations, and from the depths of midnight gloom gazes up at the back of the earth, in that region Saturn exercises the powers that are his own: cast down himself in ages past from empire in the skies and the throne of heaven, he wields as father power over the fortunes of fathers and the plight of the old” (II.929-935).

Saturn is here assigned to the fourth place for several reasons. Because the IC has been associated with the unseen source of life, it can be linked to the principle of paternity, a source that stands always already behind us. Because it forever antedates our experience, it cannot be seen. And, given that Saturn governs the fortunes of fathers and the plight of the old, he is a fitting ruler for this place. Furthermore, we see a mythological connection between Saturn and the fourth place, since Saturn is the primal Titan father struck down Zeus and the Olympian gods. He once reigned, but has now been usurped by his children, and dwells at the very bottom of the chart. And if we associate Saturn, Cronos, with Chronos, time, Saturn constitutes a fitting foundation for a nativity. For the entirety of the unfolding of the world of becoming, and hence, the entirety of our mortal lives, is grounded in the flow of time. Finally, we can discern a further a mythological association at play in the opposition between the temples of Saturn and Venus. According to Hesiod, Venus (Aphrodite) was created by Saturn’s uprising against his own father. For Venus was born of the sea foam produced from Saturn’s castration of his father Uranus. According to this story, Saturn was given a flint sickle fashioned by his mother, Earth. And when he fell upon his Father, he cut off his testicles and threw them into the sea, giving birth to Venus in the process. Hesiod explains:

“And so soon as he had cut off the members with flint and cast them from the land into the surging sea, they were swept away over the main a long time: and a white foam spread around them from the immortal flesh, and in it there grew a maiden. First she drew near holy Cythera, and from there, afterwards, she came to sea-girt Cyprus, and came forth an awful and lovely goddess, and grass grew up about her beneath her shapely feet. Her gods and men call Aphrodite, and the foam-born goddess and rich-crowned Cytherea, because she grew amid the foam, and Cytherea because she reached Cythera, and Cyprogenes because she was born in billowy Cyprus, and Philommedes because she sprang from the members. And with her went Eros, and comely Desire followed her at her birth at the first and as she went into the assembly of the gods. This honour she has from the beginning, and this is the portion allotted to her amongst men and undying gods, — the whisperings of maidens and smiles and deceits with sweet delight and love and graciousness” (Hesiod, Theogony, trans. Evelyn-White).

There is thus a mythological connection between Desire’s birth and the dismembering of Heaven. And, again, if we associate Cronos with Chronos, Time, then we can perceive him as a primordial dismembering of experience into past, present, and future. No longer does Being stand in itself, gathered in its eternal potency, but is now experienced only through the primary intentionality of time, the present always seeming to have come from the past and to be aiming towards the future. This primordial division gives birth to desire. For, one now forever looks back in nostalgia at the past, craves some future good, and, most importantly, yearns to return to the unitary ground of Being from which he has been exiled. Manilius’s pairing of Venus and Saturn with the tenth and the fourth places thus evinces a sophisticated mythological and phenomenological justification for his account of the planetary joys.

The First Place

The next cardinal pair consists of the Ascendant and Descendant. Manilius’s account of the Ascendant does not diverge from the standard model, since he identifies it with the eastern horizon and assigns Mercury to the place it defines. He maintains:

“The third cardinal, which on the same level as the Earth holds in position the shining dawn, where the stars first rise, where day returns and divides time into hours, is for this reason in the Greek world called the Horoscope, and it declines a foreign name, taking pleasure in its own. Within its domain lies the arbitrament of life and the formation of character; it will grant success to enterprises, open up the professions, and decide the early years that await men from their birth, and education they receive, and the station to which they are born, according as the planets approve and mingle their influences” (II.826-835).

Because it is identified with the horizon where stars step forth into visibility, the Ascendant is associated with the life, character, and childhood of the native. And, again, in keeping with the standard view, Manilius identifies the resulting first place with the temple of Mercury. He explains:

“This temple, Mercury, son of Maia, men say is yours, marked for its bright aspect with a designation which writers also give you for name. The one wardship is commissioned with two charges; for in it nature has placed all fortunes of children and have made dependent on it all the prayers of parents” (II. 943-947).

Mercury, with its glistening aspect, here resides in the glow of dawn.

The Seventh Place

Yet, Manilius’s model differs from the standard model in his account of the Descendant. Since the Ascendant is the place of birth, holding the life of children and the prayers of parents, Manilius argues that the Descendant should be considered as the place of death. Manilius describes it as follows:

“The last point, which puts the stars to rest after traversing heaven and, occupying the occident, looks down upon the submerged half of the sky, is concerned with the consummation of affairs and the conclusion of toil, marriages and banquets and the closing years of life, leisure and social intercourse and worship of the gods” (II.836-840).

The Descendant, then, is the horizon under which the stars sink at the end of their journey through the visible heavens. And, because it is identified with death, Manilius assigns the temple it defines, not to one of the planets, but to Pluto, the lord of the underworld. He explains:

“There remains one region, that in the setting heaven. It speeds the falling sky beneath the Earth and buries the stars. Now it looks forth on the back of the departing Sun, yet it once beheld his face; so wonder not if it is called the portal of sombre Pluto and keeps control over the end of life and death’s firm-bolted door. Here dies even even the very light of day, which the ground beneath steals away from the world and locks up captive in the dungeon of night. This temple also claims for itself the guardianship of good faith and constancy of heart. Such is the power that dwells in the abode which summons to itself and buries the Sun, thus surrendering that which it has received, and brings the day to its close” (II.946-958).

The seventh place is thus the domain of Pluto, ruling the underworld into which planets here descend. In his temple, visible light gives way to darkness and constancy and good faith are rewarded in life’s last judgment.

The Remaining Places

The Twelfth and Sixth as Empty Places

Moving on from the angular places, Manilius leaves the twelfth and sixth places empty, rather than assigning them to Saturn and Mars respectively like the standard view. Manilius describes these empty places as follows:

“The temple that is immediately above the Horoscope and the next but one to heaven’s zenith is a temple of ill omen, hostile to future activity and all too fruitful of bane; nor that alone, but like unto it will prove the abode which with confronting star shines below the occident and adjacent to it. And so that this temple should not outdo the former, each alike moves dejected from a cardinal point with the spectacle of ruin before its eyes. Each shall be a portal of toil: in one you are doomed to climb, in the other to fall” (II.864-870).

Manilius notes that these are places of ill omen. Yet he grounds this claim not in assigning them to malefics, but in pointing out that nothing resides there. The twelfth and sixth are empty temples in which there is no god to heed one’s cries. They are thus “portals of toil” through which men must struggle on their own. The twelfth place is difficult, because there one is “doomed to climb.” Having been born into the world, one must now grow and strive. And, opposite to it, the sixth place is difficult, because there, having died, one is destined “to fall” into the underworld.

The Second and Eighth as Abodes of Typhon

Manilius claims that the second and eighth places are no less difficult, designating them as the abodes of the monster Typhon. He thus again employs a deity beyond those associated with the traditional seven planets. Manilius describes Typhon’s abodes as follows:

“Not more fortunate [than the 12th or 6th place] is the portion of heaven above the occident or that opposite it below the orient; suspended, the former face downward, the latter on its back, they either fear destruction at the hands of the neighboring cardinal or will fall if cheated of its support. With justice are they held to be the dread abodes of Typhon, whom savage Earth brought forth when she gave birth to war against heaven and sons as massive as their mother appeared. Even so, the thunderbolt hurled them back to the womb, the collapsing mountains recoiled upon them, and Typhoeus was sent to the grave of his warfare and his life alike. Even his mother quakes as he blazes beneath Etna’s mount” (II.871-880).

Manilius here contends that the anxiety of the second place concerns its absolute dependence on the first place. The subject matter of the second will thus depend upon the life, birth, and vitality of the native. And Manilius associates this subject matter with Typhon’s rising up in rebellion against the Olympian gods. According to Hesiod, Typhon, a monster with one hundred snake heads sprouting from his shoulders, was born of Earth and Tartarus under the auspices of Aphrodite. 16 Hesiod proclaims: “But when Zeus had driven the Titans from heaven, huge Earth bore her youngest child Typhoeus of the love of Tartarus, by the aid of golden Aphrodite.”17 This connection to Tartarus may provide a clue to why the second and eighth places were often called “the Gates of Hades” in the Hellenistic tradition. And the mythological connection to Aphrodite may also play an important role here in light of her prominent position in the tenth.

According to the Hesiod, Typhon rises up to challenge Zeus, bringing total war to heaven and earth. Hesiod describes the battle as follows:

“From his shoulders grew an hundred heads of a snake, a fearful dragon, with dark, flickering tongues, and from under the brows of his eyes in his marvellous heads flashed fire, and fire burned from his heads as he glared. And there were voices in all his dreadful heads which uttered every kind of sound unspeakable; for at one time they made sounds such that the gods understood, but at another, the noise of a bull bellowing aloud in proud ungovernable fury; and at another, the sound of a lion, relentless of heart; and at another, sounds like whelps, wonderful to hear; and again, at another, he would hiss, so that the high mountains re-echoed. And truly a thing past help would have happened on that day, and he would have come to reign over mortals and immortals, had not the father of men and gods been quick to perceive it. But he thundered hard and mightily: and the earth around resounded terribly and the wide heaven above, and the sea and Ocean’s streams and the nether parts of the earth. Great Olympus reeled beneath the divine feet of the king as he arose and earth groaned thereat. And through the two of them heat took hold on the dark-blue sea, through the thunder and lightning, and through the fire from the monster, and the scorching winds and blazing thunderbolt. The whole earth seethed, and sky and sea: and the long waves raged along the beaches round and about, at the rush of the deathless gods: and there arose an endless shaking. Hades trembled where he rules over the dead below, and the Titans under Tartarus who live with Cronos, because of the unending clamour and the fearful strife. So when Zeus had raised up his might and seized his arms, thunder and lightning and lurid thunderbolt, he leaped form Olympus and struck him, and burned all the marvellous heads of the monster about him. But when Zeus had conquered him and lashed him with strokes, Typhoeus was hurled down, a maimed wreck, so that the huge earth groaned. And flame shot forth from the thunder- stricken lord in the dim rugged glens of the mount, when he was smitten. A great part of huge earth was scorched by the terrible vapour and melted as tin melts when heated by men’s art in channelled crucibles; or as iron, which is hardest of all things, is softened by glowing fire in mountain glens and melts in the divine earth through the strength of Hephaestus. Even so, then, the earth melted in the glow of the blazing fire. And in the bitterness of his anger Zeus cast him into wide Tartarus.”18

Manilius connects the second place to the beginning of this story. It concerns Typhon’s rising up against Zeus and challenging the new Olympian order created by the overthrow of Saturn. Typhon thus appears as the last challenge to Olympian rule. Indeed, it is only after the battle with Typhon that Zeus’s reign is ratified. Hesiod explains:

“But when the blessed gods had finished their toil, and settled by force their struggle for honours with the Titans, they pressed far-seeing Olympian Zeus to reign and to rule over them, by Earth’s prompting. So he divided their dignities amongst them.”

The mythological meaning of the second place, then, appears to concern the connection between human birth and the challenging of the Olympian order. There is something about human life that carries with it a duty and compulsion to re-value the values that have been imposed on the world by force. Remember, Zeus’s reign is not eternal. He gained his power only by overthrowing his father Cronos whom Manilius assigns to the very foundation of the chart. So, perhaps when Manilius associates Typhon with the second place, he is observing that there is a fundamental drive in man to challenge the order one has inherited and impose new values upon it. Such a desire would necessarily involve a great deal of anxiety, since the success of this godlike endeavor would depend upon the fragile body, life, and character of the native in the first place. To successfully bring down the Olympians, one would need power, courage, and tenacity that outstrip our ordinary human endowments. It is a quest reminiscent of Nietzsche’s injunction to create the Übermensch in Thus Spoke Zarathustra:

“I teach you the meaning of the overman. Man is something that shall be overcome. What have you done to overcome him?

All beings so far have created something beyond themselves; and do you want to be the ebb of this great flood and even go back to the beasts rather than overcome man? What is the ape to man? A laughingstock or a painful embarrassment. And man shall be just that for the overman: a laughingstock or a painful embarrassment. You have made your way from worm to man, and much in you is still worm. Once you were apes, and even now, too, man is more ape than any ape…..

Behold, I teach you the overman. The overman is the meaning of the earth. Let your will say: the overman shall be the meaning of the earth!” (Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Prologue 3, trans. Kaufmann).

Nietzsche’s account here parallels Hesiod’s in connecting the Übermensch to the earth. Just as Typhon was born of earth to challenge the Olympian gods, so too is the Übermensch conceived to give meaning to the earth. Man is impelled to overcome himself and overturn the inherited norms that strike him as foolish and wrong. Perhaps this primordial drive is what Manilius has in view when he identifies the second place with Typhon’s revolt against the Olympians.

Alternatively, a more philosophical reading of the myth follows Plato’s account of the tripartite soul in Book IX of the Republic, where he likens human nature to an amalgamation of three creatures (588c-590d). The first creature is a human being, corresponding to the rational soul. The second is a lion, corresponding to the spirited soul. And the third creature, one corresponding to the appetitive soul, Plato likens to a many headed beast. Socrates claims that justice consists of these three elements of the soul living in harmony, the human part educating and ruling the others. When understood in these terms, Manilius’s identification of the second place with Typhon’s rebellion could call attention to the fact that our incarnate life carries with it a set of appetites, appetites that lead to anxiety, since they depend on our body, life, and character for fulfillment. Manilius would, in this manner, be presenting something like a Freudian picture of unconscious19 libido that generates anxiety. However, there is an important difference between the Manilian and Freudian pictures, since each explicates the grounding relation in different directions. According to Freud, the ego supervenes on unconscious libidinal forces, thereby making conscious life and personal character mere slaves to unconscious impulses. In contrast, for Manilius, the second place is one of anxiety, because it depends on the conscious life and character of the native for its fulfillment. Appetites depend on the subjects who have them, not the other way around. They “will fall if cheated” of the Helm’s “support”. One advantage of this Platonic reading is that it provides a straightforward account of why the second place was traditionally associated with money. For Plato observes that money is the chief desire of the appetitive soul in cultures like ours, when he claims that the appetitive “is the largest part in each person’s soul and is by nature most insatiable for money” (Republic IV. 442a).

Opposite the second place is the eighth. Whereas Manilius associates the former with Typhon rising up against Zeus, he associates the latter with his falling in judgment, ablaze with divine fire as he plunges into Mt. Etna. Manilus depicts the scene as follows:

“The thunderbolt hurled them back to the womb, the collapsing mountains recoiled upon them, and Typhoeus was sent to the grave of his warfare and his life alike. Even his mother quakes as he blazes beneath Etna’s mount” (II.877-880).

Manilius’s account of the eighth place thus explains why this place would traditionally be associated with justice, and, like the second, be called “the Gates of Hades”. For, in being associated with Typhon’s fall, it reminds us of judgment and the justice of heaven. And, as the place of falling into Hades (which Manilius associates with the seventh), it would constitute the portal to the realm of the dead.

To continue our mythological interpretation sketched for the second place, we can here understand the eighth place as concerning the fact that, though something in us compels us to transcend the order we inherit, we, as finite beings, will nonetheless face judgment for our actions. The paradise we seek will never be erected on earth by our own efforts, since true transfiguration comes by grace alone. Perhaps Typhon saw this as he was consumed by celestial lightning. Perhaps the tongues of fire burning over his monstrous heads were also the flames of ecstasy as he, falling ever deeper into Mt. Etna’s central fire, melted back into the eternal ground of Being.

Or, to use the more Platonic interpretation sketched earlier, we could say that the eighth place represents the temple in which the appetitive soul is transmuted by divine power, its lower impulses purged in preparation for death.

Whereas the anxiety of the second place is grounded in its dependence on the Helm, the anxiety of the eighth place derives from its standing face to face with the place of death, fearing “destruction at the hands of the neighboring cardinal”.

The Third and Ninth Places

Manilius’s account of the third and ninth places largely corresponds to the standard model. He gives the ninth place to the Sun, whom he refers to as Phoebus Apollo, stipulating that:

“The stars that follow midday, where the height of heaven first slopes downward and bows from the summit, these Phoebus nourishes with his splendor; and it is by Phoebus’s influence that they decree what ill or hap our bodies take beneath his rays. This region is called by the Greek word signifying God” (II.905-910).

We thus have a standard assignment of the Sun to the ninth place, and a standard name for this place as the place of God. Yet, it is still worth pondering their implications within the specific mythological landscape set forth by Manilius. For example, we might wonder what it says about the conflict between Zeus and Typhon, when Manilius gives the place of God not to Zeus, but to Phoebus Apollo (in his identification with the Sun). At the very least, Zeus, and the recent Olympian order he represents is not identical with God. And the Platonist would likely call to mind the familiar association between the Sun and the Form of the Good. And it is also worth noting that God’s temple is the one in which planets begin their descent into the Hades, the unseen world of spirit. This calls to mind Socrates’ remark before his death urging his friend Crito to offer a cock to Asclepius in thanks for his impending separation from his body.

Opposite the ninth place is the third, which Manilius gives to the Moon. Manilius declares:

“Shining face to face with it is that part of heaven which rises first from the bottom-most regions and brings back the sky once more: it controls the fortunes and fate of brothers; and it acknowledges the Moon for its mistress, who beholds her brother’s realms shining on her from the other side of heaven and who reflects human mortality in the dying edges of her face. Goddess is the name in Roman speech to be given to this region, whilst the Greeks call it by the same word in their language” (II.910-917).

Manilius once more offers a standard account of the third place by giving it to the Moon and calling it the temple of “The Goddess”. But again, it is worth exploring how this assignment functions specifically within the Manilian scheme. For instance, he appears to give a novel account of why the third place concerns siblings, when he claims that, since sun and moon are brother and sister, and she looks on her brother shining from the opposite temple, he Moon, as a reflected light, will transmit what she sees, and so her own place will concern the fates of brothers. Or, again, the emphasis on the Moon’s connection to mortality also appears to be unique to Manilius.

The Fifth and Eleventh places

Finally, Manilius’s account of the eleventh and fifth places corresponds, in part, to the standard view. But it but also departs from it in significant respects. Manilius agrees with the standard model in assigning Jupiter to the eleventh place, yet he labels this temple, “Happy Fortune” rather than “Good Daimon”. He explains:

“The temple immediately behind the summit of bright heaven, and (not to be outdone by its neighbor) of braver hope, surges ever higher, being ambitious for the prize and triumphant over the earlier temples: consummation attends the topmost abode, and no movement save for the worse can it make, nor it aught left for it to aspire to. There is thus small cause for wonder, if the station nearest the zenith, and more secure than it, is blessed with the lot of Happy Fortune. So most closely does our language approach the richness of Greek and render name for name. In this temple dwells Jupiter: let its ruler convince you that it is to be reverenced” (II.881-890).

The eleventh place is fortunate, since, though a planet located therein has yet to reach the height of its powers, it nonetheless strives to do so and has not yet begun to decline as do planets in the summit of the tenth.

Manilius’s account also contrasts with the standard view in assigning Mars rather than Venus to the fifth place. Though Manilius is not explicit about this assignment, he nonetheless clearly indicates that he intends Mars to dwell in the fifth. Note first that Mars is the only planet which is not explicitly assigned to a place. Moreover, Manilius asks us to consider the divinity that resides in the fifth place, but does not name it explicitly. He instructs:

“Lay carefully in your mind the abode and the divinity and appellation of the puissant abode, so that hereafter the knowledge may be put to great use” (II.898-900).

Now, given that Manilius assumes that we know the deity to whom he is referring, it is reasonable to infer that he intends to refer to Mars, the only remaining planet.

A second consideration indicating that Manilius gives Mars the fifth is that he characterizes this place in terms of warfare, a quintessentially martial activity. In the passage cited above, Manilius describes the fifth place as puissant (potentis), i.e. effective and powerful. And he claims that a secret war on health is waged within it. “Here largely abide the changes in our health and the warfare (pugnatia) waged by the unseen weapons of disease” (II.901-902). Since Mars is the god of war, it is likely that Manilius had him in mind when making these remarks.

Third, on the standard model, the place of Mars’ rejoicing is associated with illness. So the fact that Manilius associates illness with the fifth place is further evidence that he intends it as Mars’s abode. And, finally, a similar case can be made from the fact that Manilius refers to the fifth place as “Daemonie”, which was used by other astrologers to refer to the joy of Mars in the sixth place.20 There is thus considerable evidence for interpreting Manilius as assigning Mars to the fifth.

In addition to its association with illness, Manilius explicates the meaning of the fifth place as follows:

“[This temple] is thrust below the world and adjoins the nadir of the submerged heaven, and which shines on the opposite region: wearied after completion of active service it is again marked out for a further term of toil, as it waits to shoulder the yoke of the cardinal temple and its role of power: not as yet does it feel the weight of the world, but already aspires to that honor” (II.891-896).

The fifth place is thus considered a point of exhaustion after an entire cycle has been completed. For, if we begin at the foundation in the fourth place, the fifth would be the last position before beginning another revolution through the wheel. The weariness that attends this position may be a further reason why Manilius associates it with Mars and disease. Only a warrior would have the stamina to withstand this position without giving up in exhaustion, and one can think of disease as the affliction of a weary body.

Overall Themes in the Manilius’s Schema

Manilius thus provides a coherent and insightful account of the planetary joys. His Astronomica offers not only an alternative schematization of the joys, but also a set of plausible justifications for the planetary assignments contained therein. When we consider Manilius’s account objectively, we find we are far from the domain of mere poetic embellishment. Would anyone judge, for example, Manilius’s justification for assigning Saturn to the fourth because of its association with fathers and foundations to be less convincing than Rhetorius’s putative justification for assigning Saturn to the twelfth because Saturn rules water and water breaks before a child is born?21

In addition to the particular arguments Manilius sets forth, his schema displays a variety of notworthy systematic features. First, Manilius’s model contrasts with the standard view in its orientatin to the hemispheres. According to the standard view, the upper hemisphere constitutes the realm of Daimon,22 since the twelfth place is called the place of the “Bad Daimon” and the eleventh that of the “Good Daimon”. Likewise, the standard view identifies the lower hemisphere with the domain of Fortune, calling the sixth place “Bad Fortune” and the fifth “Good fortune.” Manilius’s schema, in contrast, reverses this orientation.23 For Manilius associates the visible heavens with the domain of Fortune, calling the eleventh the place of “Happy Fortune”, and the tenth “Fortune” itself. In contrast, he identifies the lower hemisphere, the world that we cannot see, with the domain of the Daimon, naming the fourth “Daimonium” and the fifth “Daimonie.”

Hence, Manilius identifies the realm of the Daimon, not with what is physically, but what is spiritually above us. We can again see Manilius as echoing one of Plato’s claims in the Republic. In book VII, when Glaucon praises astronomy because it “compels the soul to look upward and leads it from things here to things there [in heaven]”, Socrates argues the opposite, contending that “as it’s practiced today…it [astronomy] makes the soul look very much downward” (529a). For, even though the stars are physically above us, they are nonetheless a part of the physical world, and thus metaphysically below the soul. Socrates explains:

“In my opinion, your conception of ‘higher studies’ is a good deal too generous, for if someone were to study something by leaning on his head back and studying ornaments on the ceiling, it looks as though you’d say he’s studying not with his eyes but with his understanding. Perhaps you’re right, and I’m foolish, but I can’t conceive of any subject making the soul look upward except one concerned with that which is, and that which is is invisible. If anyone attempts to learn something about sensible things, whether by gaping upward or squinting downward, I’d claim—since there’s no knowledge of such things—that he never leans anything and that, even if he studies lying on is back on the ground or floating on it in the sea, his soul is not looking up but down” (Republic 529b-c).

We can imagine Manilius making a similar claim when asked why the Daimonic realm should be identified with the invisible world and not the visible sky overhead. He could assert, in Platonic fashion, that the unseen realm is what grounds and supports the material outworking of fortune observed in the physical world.

This shift in perspective between the standard account of the planetary joys and Manilius’s view is akin to the one that occurs in Dante’s Paradiso when Dante enters the primum mobile after ascending through the celestial spheres. There, he beholds a metaphysical order apparently inverse to the physical order of the cosmos. Whereas, in the medieval world, the earth was physically the center of the universe, with each of the celestial spheres constituting a region further and further from that center, Dante now sees that the regions farthest from earth are closest to the true metaphysical center of the cosmos—God, the unmoved mover, for whom all beings yearn.24 C.S. Lewis aptly describes the dual nature of this medieval perspective in the Discarded Image when he observes:

“Whatever else a modern feels when he looks at the night sky, he certainly feels that he is looking out—like one looking out from the saloon entrance on to the dark and lonely moors. But if you accepted the Medieval Model you would feel like one looking in. The earth is ‘outside the city wall’. When the sun is up he dazzles us and we cannot see inside. Darkness, our own darkness, draws the veil and we catch a glimpse of the high pomps within; the vast, lighted concavity filled with music and life. And, looking in, we do not see… ‘the army of unalterable law’, but rather the revelry of insatiable love. We are watching the activity of creatures whose experience we can only lamely compare to that of one in the act of drinking, his thirst delighted yet not quenched. For in them the highest of faculties is always exercised without impediment on the noblest object; without satiety, since they can never completely make His perfection their own, yet never frustrated, since at every moment they approximate to Him in the fullest measure of which their nature is capable…. Then, laying aside whatever Theology or Atheology you held before, run your mind up heaven by heaven to Him who is really the center, to your senses the circumference, of all; the quarry whom all these untiring huntsmen pursue, the candle to whom all these moths move yet are not burned.”25

Such a model may well also underlie Manilius’s alternative account of the planetary joys.

And there are further systematic advantages to Manilius’s model. For, instead of following the standard view in arranging planets by sect (placing nocturnal planets below the horizon, diurnal planets above the horizon, the changeable Mercury in the first place), Manilius situates the benefics above the horizon, and the malefics below the horizon. Yet, sect considerations still enter into Manilius’s account, since, in it, malefics and benefics oppose each other according to sect. Saturn, the diurnal malefic opposes Venus the nocturnal benefic, the former residing in the fourth and the latter in the tenth. And Jupiter the diurnal benefic opposes Mars the nocturnal malefic, the former rejoicing in the eleventh and the latter in the fifth. Manilius’s schema thus justifies the observation of many contemporary Hellenistic astrologers that contrary sect malefics tend to be the most difficult planets, and that benefics of sect tend to do the most good. Manilius’s account thus has the advantage of explicitly justifying this observation. Indeed, one might even argue that it makes more sense than the oppositions encoded in the standard model, wherein Jupiter opposes Venus, and Saturn opposes Mars.

Manilius’s Sources: Esoteric Pythagoreanism.

Manilius’s alternative account of the planetary joys thus displays considerable merit when examined on its own terms. I will now contend that it has the additional advantage of preserving an even older tradition of astrology, esoteric Pythagoreanism.26 Pythagoras was a philosopher and sage who claimed that the visible world of experience was grounded in an invisible world of number, and his work formed the foundation for later Platonic thought. Understanding the Pythagorean background of Manilius’s account will allow us to further understand why Manilius’s model reverses the orientation of the standard view, situating the realm of the Daimon below the horizon rather than above it.

Several lines of evidence lead us to suspect that Manilius’s model is informed by a Pythagorean perspective.

First, it is important to note that Manilius assigns deities to ten of the twelve places. To fill the requisite number of places, Manilius was forced to employ gods in addition to those corresponding to the seven traditional planets. This suggests that there was a symbolic importance to assigning divinities to specifically ten places. This emphasis on the number ten makes sense when we view Manilius’s account from a Pythagorean perspective, since ten was a holy number for Pythagoreans, being associated with the Tetractys. Indeed, Aristotle reports that Pythagoreans inserted additional astronomical bodies (the Central Fire and Antichthon ) into their model of the universe to make the number of bodies correspond to the number ten. We can thus think of whoever designed Manilius’s model as acting in a similar manner, adding extra deities to ensure that exactly ten places were occupied.27

Second, positing a Pythagorean background for Manilius’s model makes sense of its conspicuous reference to mount Etna and the claim that Typhon quakes beneath it (II.880). For Mt. Etna was an important ritual site for Pythagoreans. Indeed, the Pythagorean philosopher Empedocles was even said have been deified by leaping into the flames of Mt. Etna.28 Historian Peter Kingsley notes that Etna was considered by both Greeks and Romans to be a place linked “both with the underworld and with the heavens” and to have been of significant ritual importance.29

Third, it explains the prominence assigned to places associated with the underworld in Manilius’s model. The second and eighth houses, commonly called the “Gates of Hades”, are associated with Typhon’s rising up from the underworld in rebellion and his falling back to it after his failed coup, the latter being associated with Mount Etna as noted earlier. Furthermore, Pluto himself, lord of the underworld, keeps guard over the seventh place, a place Manilius identifies with “death’s firm-bolted door”. And Saturn, also in Tartarus with the Titans, rejoices in the fourth place which Manilius claims is the very foundation of the chart. The aspects between these places also highlight their importance. Saturn dominates Pluto by a superior square, trines the judgment place of Typhon in the eighth, and sextiles the rising up of Typhon in the second. This emphasis on the realm of the dead, the spiritual world we cannot see, makes sense once we place Manilius’s model in a Pythagorean framework, since the grounding of the visible world in an unseen world of the dead was a common theme in esoteric Pythagoreanism. Kingsley once more observes:

“Contrary to what is often supposed, the immediate aspiration on the part of Pythagoreans for contact with the divine appears to have been directed in the first instance to the underworld, to the gods below…; and in antiquity the best way of actually making contact with divinities of the underworld was through the practice of ‘incubation’–of awaiting a dream or vision while sleeping, as a rule, either on or even inside the earth.”30

And we see this theme at play in the Pythagorean identification of the universe’s central fire with the guardhouse of Zeus. Aristotle, for example, reports:

“The Pythagoreans have a further reason [for assigning the central fire, rather than the earth, to the center of the universe]. They hold that the most important part of the universe, which is the center, should be most strictly guarded, and name it, or rather the fire which occupies that place, the ‘Guard-house of Zeus’” (Aristotle, de Caelo, II.13.1, 293b1 trans. Stocks, modified).

And this guardhouse of Zeus, argues Kingsley, was identified with Tartarus in the ancient world.31 This Pythagorean context allows us to explain why Manilus would prioritize the earth below the horizon and the unseen realm of the dead in his planetary joys scheme.

Fourth, a Pythagorean framework can also explain why Manilius assigns Venus to the tenth. In his book, Reality, Kingsley argues that the pre-Socratic philosopher Parmenides should be understood as operating within the Pythagorean tradition. And Parmenides famous poem, On Nature, describes two ontological and epistemic paths: the way of truth, in which one grasps unchanging Being, and the way of opinion, in which one beholds the changing world of experience. Kingsley follows Plutarch in identifying the goddess who speaks in the second half of the poem with Aphrodite (Venus). He contends:

“This quality of elusive beauty in the world Parmenides describes, as well as in the way he describes it, should come as no surprise. For there is one very particular divine being whom he presented as ruling our visible universe.

That’s the goddess Aphrodite, queen of infinitely tempting beauty and love and charm.”32

And, he notes:

“Aphrodite was not just a divinity of beauty. She was also the supreme goddess of deception and illusion.

She is the great charmer who loves seducing gods, as well as humans, through the glitter of appearance; through desire and attraction and love. As for her sweet shimmer and the delicate magic of her sheer charm, they are precisely what gives her deceptions their ruthless power. Greeks understood very well that underneath the beautiful surface she is a superb hunter, expert at trapping and cunningly binding her prey.

And the one term that best summed up the effects of her deception on her victims is a word we should already be familiar with: amechania, ‘helplessness.’”33

This background explains why Venus would be placed in the tenth in Manilius’s model, since she reigns in the place of Fortune, “plying her own weapons” from on high (II.926).34

Finally, positing a background of esoteric Pythagoreanism would explain why Manilius shifts the polarity of the standard view. While the standard model, as noted earlier, associates the realm of the Daimon with the visible sky above, and fortune with what is hidden from view in the earth, Manilius associates realm of the Daimon with the unseen world, the realm of the dead veiled from mortal eyes in earth’s central fire. This, as noted previously, was a key element of esoteric Pythagorean philosophy. Furthermore, this Pythagorean background also explains why the malefics would be associated with the Daimonic realm in Manilius’s account. Malefics are considered malefic because they tend to kill us. But, if the unseen ground of the visible world is identified with the realm of the dead, then it makes sense that Malefics would reside here, since they translate us to that world, separating soul from body.35

Conclusion

Manilius’s alternative account of the planetary joys is thus worthy of careful consideration. His account should not be dismissed as the idle musings of a second rate poet, but studied as a sophisticated account of how the places derive their meanings in the Hellenistic tradition. I’d like to conclude with three brief lessons we can draw from the arguments sketched above. First, cases such as this should remind us that multiple competing systems were at play in what is now called “Hellenistic astrology”. It is a mistake to presuppose that the writings of Valens constitute a normative standard by which to judge all other systems. Given that diverse astrological systems were practiced in antiquity, it is necessary to evaluate each of them on their own terms, and come to our own conclusions about which account is best for any given domain. Second, the esoteric Pythagorean background of Manilius’s account should remind us that, at its inception, astrology, philosophy, and spirituality were inseparable. We would do well to remember this connection as we try to revive the practice of Hellenistic astrology. If we sever astrology from philosophical contemplation and spiritual practice, we will never practice it in the same spirit as the ancients. And, finally, it is worth considering whether Manilius’s alternative account of the planetary joys can help to bridge the gap between ancient and modern astrology. For his account assigns deities to three places in addition to the seven acknowledged by the standard model. And, it just so happens that contemporary astrology employs three additional planets: Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto. Furthermore, there appears to be an archetypal resonance between Manilius’s account of the these additional places and the energies of the modern planets. Manilius assigns the second place to Typhon rising in rebellion against the Olympian order, and modern astrologers often describe Uranus as a rebel, rising up like Prometheus to challenge the gods. Likewise, Manilius gives the eighth place to Typhon as he falls flaming from heaven in judgment, plunging into Mt. Etna wherein solid earth dissolves in magma.36 And modern astrologers associate Neptune with the dissolution of the ego and spiritual ecstasy. Neptune can thus be said to rejoice in the eighth, exulting in his dissolution in a kind of a planetary Liebestod. And, finally, Manilius assigns Pluto to the seventh place, a place associated with sex and death, precisely the significations modern astrologers give to the planet Pluto. Manilius’s alternative joys schema thus provides us with a promising way to incorporate the modern planets within a broadly Hellenistic framework for astrology. One might attribute this kind of synchronicity to a lucky historical accident, but I suspect that there are deeper forces at work here. If one believes that heavenly phenomena can predict earthly events, would it be so implausible to think that an ancient esoteric philosopher could have foreseen contemporary astrological practice?

Peter Yong, Ph.D.

[The Image used in the thumbnail for this essay is a picture of Hades and Persephone in a shrine at Locri. It was taken by Almare and is under a creative commons license. It can be found here: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Locri_Pinax_Of_Persephone_And_Hades.jpg ]

1Brennan, Hellenistic Astrology, 84.

2Ibid., 105.

3Ibid., 106.

4Ibid., 120.

5Deborah Houlding is notable exception in this regard, since she takes Manilius’s account seriously in her book The Houses: Temples of the Sky.

6Schmidt, The Facets of Fate, n.11. One can imagine Manilius making a similar evaluation of the schema Schmidt sets forth. For, how else should one characterize Schmidt’s attempt to ground the meanings of the places in lexical speculations about the word “φορά” without any attempt to argue that these meanings are mutually exclusive or jointly exhaustive, or that they could in any way constitute a whole while being presented as “contingent”, “accidental”, and “ultimately unintelligible”?

7Ptolemy, Tetrabiblos I.20-21.

8Porphyry argues “Concerning the peculiar daemon, it must be inquired how he is imparted by the lord of the geniture, and according to what kind of efflux, or life, or power, he descends from him to us? And also, whether he exists, or does not exist? And whether the invention of the lord of the geniture is impossible, or possible? For if it is possible he is happy, who having learned the scheme of his nativity, and knowing his proper daemon, becomes liberated from fate.The canons, also, of genethliology [or prediction from the natal day] are innumerable and incomprehensible. And the knowledge of this mathematical science cannot be obtained; for there is much dissonance concerning it, and Chaeremon and many others have written against it. But the discovery of the lord, or lords, of the geniture, if there are more than one in a nativity, is nearly granted by astrologers themselves to be unattainable, and yet they say that on this the knowledge of the proper daemon depends” (Letter to Anebo, trans. Taylor).

9One struggles to give a charitable interpretation of the inference here. It appears to be something like, x is difficult, thus x lacks a true foundation.

10Indeed, Valens himself evidently felt so threatened by these rivals that he cursed those who would use his work. This brings up a further question regarding the adoption of Valens as our primary source for Hellenistic astrology. If a contemporary spiritual teacher were to exhibit such an attitude, would you follow them uncritically, or would you not rather hold their subsequent claims under considerable scrutiny?

11Brennan, The Planetary Joys and the Origins of the Significations of the Houses and Triplicities, 25.

12Though he identifies the Sun with Phoebus Apollo, thus differing from the standard view.

13Though he calls this place “Happy Fortune”, again diverging from the standard view.

14CHORUS MYSTICUS: Alles Vergängliche/ Ist nur ein Gleichnis;/ Das Unzulängliche,/ Hier wird’s Ereignis; /Das Unbeschreibliche,/ Hier ist’s getan;/ Das Ewig-Weibliche/ Zieht uns hinan.

15C.S. Lewis, The Last Battle.

16Hesiod, Theogony.

17Hesiod, Theogony.

18Hesiod, Theogony.

19Unconscious because the second house is in aversion to the first.

20See footnote d in Houseman’s translation, p. 153.

21“And it [the 12th] is chosen as the house of Saturn, inasmuch as through the pouring out of waters the fetus is expelled”, Rhetorius, Compendium, 57.

22Often misleadingly translated as “Spirit”.

23“And the way up is the way down, the way forward is the way back./ You cannot face it steadily, but this thing is sure,/ That time is no healer: the patient is no longer here.” T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets: Dry Salvages, III.

24See Paradiso, Canto 28. A good analysis can also be found here: https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/paradiso/paradiso-28/

25C.S. Lewis, The Discarded Image.

26This should not be surprising since Pythagoreans had long used astrological speculations in their work. See, F. Boll, Aus der Offenbarung Johannis. Hellenistische Studien zum Weltbild der Apokalypse, p.40 n.1.

27“And all the properties of numbers and scales which they could show to agree with the attributes and parts of the whole arrangement of the heavens, they collected and fitted into their scheme; and if there was a gap anywhere, they readily made additions so as to make their whole theory coherent. E.g. as the number 10 is thought to be perfect and to comprise the whole nature of numbers, they say that the bodies which move throughout he heavens are ten, but as the visible bodies are only nine, to meet this they invent a tenth—the ‘counter-earth’. We have discussed these matters more exactly elsewhere” (Aristotle, Metaphysics I.5, trans. Ross).

28I discuss the death of Empedocles in my essay “The Life and Philosophy of Empedocles”. https://premieretat.com/the-life-and-philosophy-of-empedocles/

29Kingsley, Ancient Philosophy, Mystery, and Magic: Empedocles and the Pythagorean Tradition, 280.

30Ibid., 283-284.

31Ibid., 187-189.

32Kingsley, Reality, 214.

33Ibid.

34Positing a Pythagorean background also makes sense of why Venus and Saturn are opposed in Manilius’s schema. For, one of the esoteric pronouncements of the Pythagoreans was that “the sea is a tear of Kronos” (Porphyry, Life of Pythagoras, § 41. Trans. Gutherie). This image reminds one of the sea foam from which Aphrodite was born after Kronos castrated his father. The two are thus mythologically joined, and this joining is encoded in the astrology.

35Even the Moon is connected to mortality in Manilius’s account. Manilius observes that the third place “acknowledges the Moon for its mistress, who… reflects human mortality in the dying edges of her face” (II.915).

36Hesiod describes the melting of the earth explicitly in the Theogony. “A great part of huge earth was scorched by the terrible vapor and melted as tin melts when heated by men’s art in channeled crucibles; or as iron, which is hardest of all things, is softened by glowing fire in mountain glens and melts in the divine earth through the strength of Hephaestus. Even so, then, the earth melted in the glow of the blazing fire. And in the bitterness of his anger Zeus cast him into wide Tartarus.”